Viral Myths: a response to my critics (Part 2)

SUGGESTED

In a previous post, I have already addressed the strange idea that comparing the performance of the National Health Service to that of other health systems is somehow an “attack” on doctors and nurses. In this post, I will address another response which I keep receiving, namely, the idea that I am blaming the NHS for what are really the failures of the government. The NHS, in this version of events, has done the most amazing job it possibly could have, given the constraints. The government, however, has undermined it at every step of the way. My critics claim that I am letting the real culprit – the government – off the hook, in order to pin the blame on the NHS, thus cynically using the pandemic to peddle an anti-NHS agenda.

I am intrigued where they get this idea from, because it cannot be from my report, which is crystal-clear on this point:

“It would […] be absurd to say that a high excess death rate is ‘proof’ that a country has a bad healthcare system. Pandemic-induced excess deaths are not specifically, or even predominantly, attributable to the healthcare system. A myriad of other factors come into play, such as the type and timing of lockdown policies, of social distancing measures, of travel bans and quarantining measures, the effectiveness of contact tracing, demographics, employment structure, geography, scope and uptake of furlough schemes, the clarity of scientific advice and guidance, compliance with that advice, and, of course, brute luck. […] We obviously cannot blame the NHS for the fact that the UK introduced its first lockdown later than many of its neighbours. We cannot blame the NHS for the fact that the UK government decided to keep its large hub airports open, or for the lax enforcement of quarantining measures. We cannot blame the NHS for the effects of the misguided ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme. (pp. 42-43)”

And while I have lots of positive things to say about Taiwan’s Covid record, I also make clear that

“we cannot specifically credit the Taiwanese healthcare system for that. Since Taiwan’s overall pandemic response has been so effective, its healthcare system never came under exceptional strain. The heavy lifting was done elsewhere. (p. 46)”

We cannot isolate the contribution of the healthcare system to a country’s pandemic performance. We do not know how Britain would have fared if we had had healthcare system X, Y or Z instead of the National Health Service.

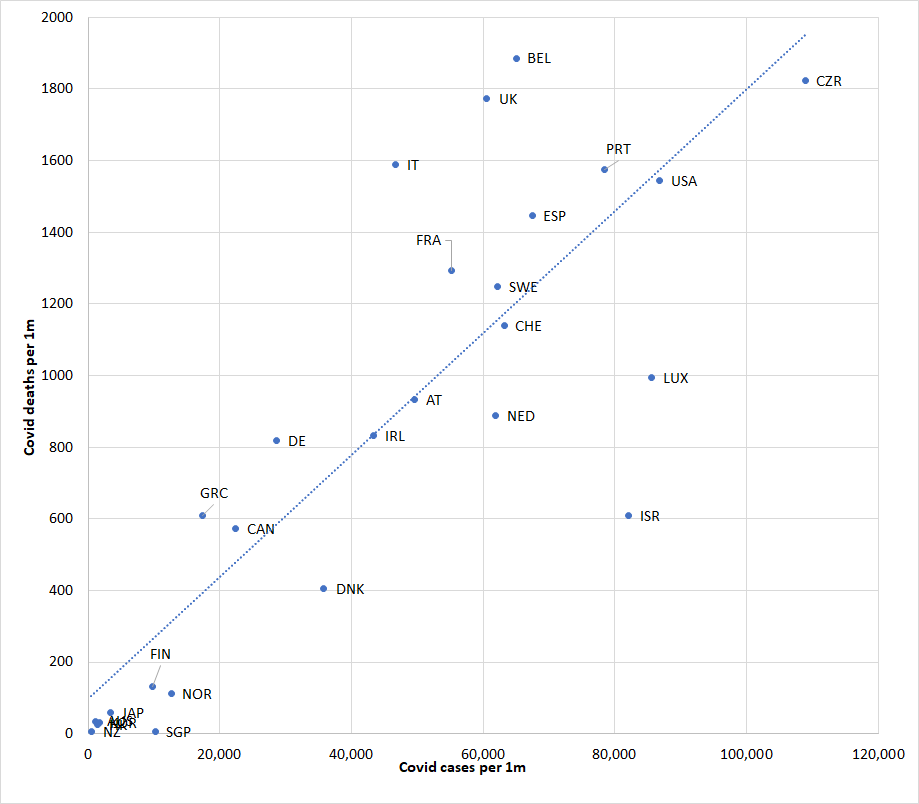

What we can do, however, is narrow things down a bit. The graph below shows the correlation between Covid prevalence (that is, the number of confirmed Covid cases) and Covid deaths (both per 1 million inhabitants). (Feel free to play around with the data by changing the selection of countries – there is nothing special about this one.)

Graph: Covid prevalence vs Covid deaths

-based on figures from Worldometer

That correlation is, unsurprisingly, fairly high. The countries that had the lowest Covid death rates (Taiwan, Singapore, New Zealand, Hong Kong, South Korea, Australia and Japan) achieved this, in the main, by containing the spread of the virus. The countries that suffered the highest Covid death rates did so, in large part, because they lost control of the spread of the virus.

We can treat Covid prevalence as an external constraint which is completely outside of the health system’s control. We can hold prevalence constant, and restrict comparisons only to countries with similar levels of Covid prevalence. We can, for example, disregard all countries with fewer than 40,000 confirmed Covid cases per 1m people, or 50,000, or 60,000, and compare the UK only to the remainder. That way, we would still not “isolate” the healthcare system’s contribution. But it would now be somewhat implausible to claim that differences in death rates among the remaining countries have nothing whatsoever to do with the healthcare system.

Wherever you want to set the threshold, and whichever way you want to split the data – the UK remains close to the top of the remaining set of countries. The Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Luxembourg and the US all had to deal with higher Covid infection rates than the UK. Still, they all managed to keep death rates below the UK level. More precisely, Switzerland’s Covid death rate is a third below the UK’s, the Dutch Covid death rate is only half the UK’s, and the Israeli one a mere one third of that, again, despite these countries’ higher caseloads.

Can we conclude that our death rate would have been substantially lower if we had a healthcare system more like theirs? No – because that would be a bit of a stretch. But it would be an even bigger stretch to conclude that the NHS has been some kind of superstar performer, which we should all applaud and rally around.

I haven’t made many friends with my assessment that “there is no rational basis for the adulation the NHS is currently receiving, and no reason to be ‘grateful’ for the fact that we have it. […] There is nothing special about the NHS, neither during this pandemic, nor at any other time. (p. 52)”

But I stand by those words.

4 thoughts on “Viral Myths: a response to my critics (Part 2)”

Comments are closed.

A major problem with this analysis is the assumption that countries attibute deaths to Covid using the same criteria. It is well known this is not true. For example, Belgium’s high death rate is largely a result of this artifact.

Ben – have a look at this dataset here, which compares recorded Covid deaths to excess deaths.

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/coronavirus-excess-deaths-tracker

For a lot of low- and middle-income countries, it makes a huge difference. For high-income countries, however, the two are almost perfectly correlated. That’s true over time, it’s true across countries, and it’s true across regions within countries.

When Covid deaths go up, excess deaths go up. When Covid deaths go down, excess deaths go down. When Covid deaths are clustered in particular regions, excess death figures are also clustered in the same regions. As long as you’re only comparing developed countries (which is what I do in the above article and in the report itself), the measurement/classification problems don’t apply.

It might also be instructive to look at variations in death rates following hospital admission between different hospitals and regions in the UK and also compared to other countries . I am led to believe that the death rates varied wildly in the UK which does suggest that some hospitals may have performed poorly (albeit you would expect some variation because of uncertainties initially as to best treatment practice – but the time it takes to disseminate best practice can tell us quite a lot about the efficiency of a healthcare system).

HJ – it might do, but whether hospitals admit may also be a feature of the healthcare system