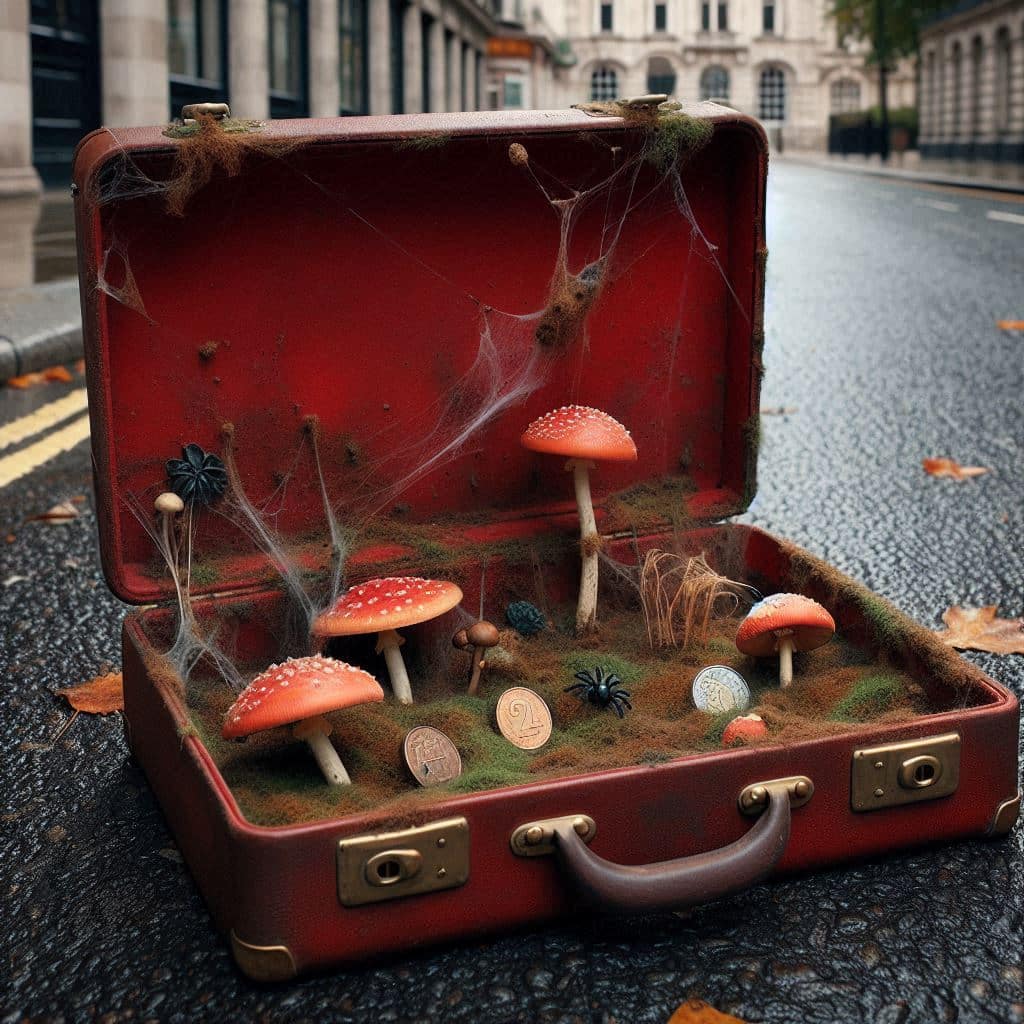

Some thoughts on the Budget

SUGGESTED

Budgets are supposed to be delivered in March, just before the start of the new fiscal year. So what if there’s a new government? Labour’s tax and public spending priorities are not so radically different from those of the Conservatives that they could not have let the March 2024 budget run its course, with the usual adjustments here and there. What we have seen is simply the replacement of a government which claims to believe in a smaller state, but is not prepared to rethink anything the state does, with a government that believes in a bigger state, and acts like it.

The economic impact of the new budget is easily summarised. Government spending will permanently rise by about 2.2 percentage points of GDP, just over half of which will come from tax increases, the remainder will come from increased borrowing. About two thirds of the increase represents consumptive spending, the remainder being public investment. According to the OBR’s forecast, the budget will boost economic growth slightly for two years, but that effect then wears off, and drops to zero. This is because the increase in government spending will be wholly offset by a decrease in private household consumption and business investment, which means that the budget is just a straightforward zero-sum transfer from the private to the public sector.

It could hardly be otherwise. This is a Keynesian budget, but we are not in a Keynesian situation. Keynesianism, if you believe in that sort of thing, can work when there is a lot of unused spare capacity in the economy. According to the OBR’s modelling, we are not in that kind of economy. We are already close to the maximum economic output that our current productive capacity allows. Unless we improve that capacity – this is about as good as it gets.

A recurring theme on this blog is that the main drag on UK growth is not on the fiscal side. It is the UK’s inability to build anything. This is why a genuine growth impulse was never going to come from any budget. We are not in a situation where we could boost output with a Laffer Curve-style budget. But neither are we in a situation where could boost output with a Mazzucato-style budget. The problem is not that Britain invests too little in things like infrastructure projects, but that we get too little infrastructure from any given budget.

In the months around the election, it looked as if Labour were flirting with supply-side YIMBYism. That would be outside of their comfort zone, and it was clearly never a deeply-held conviction. But for a while, it looked plausible enough. Labour can get away with supply-side measures, because they rely on a younger electoral coalition which is less prone to NIMBYism. They also have few other options. They want to splash out on public services, ideally without either visible tax hikes or large amounts of additional borrowing. Under the current circumstances, the only way in which you can realistically do this is by boosting growth through YIMBY-style supply-side reforms.

If Labour now retreat into their comfort zone and settle for a conventional tax-and-spend agenda, “Starmerism”, as an economic project, will be finished before it even got off the ground.