Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short?! (Part 3)

SUGGESTED

Alston makes many claims about living standards. Some turn out to be without foundation and based on repeating what advocates have told him. For instance, Alston writes:

“It is hardly surprising that civil society has reported unheard-of levels of loneliness and isolation, prompting the Government to appoint a Minister for Suicide Prevention.”

Loneliness is not rising – around 5-6 per cent of the population are lonely often or always, with no evidence of an upward trend, according to the ONS. It is nigh-on 5-6 per cent every year; hardly “unheard-of”. Moreover, the suicide rate is at almost record low levels; it rose slightly with the recession and has been declining since.

In his first report, Alston claimed 1.5 million people were destitute. This was in fact, a misrepresentation of the research he was quoting from. What the JRF research he cited actually found was that 1.5 million people were destitute at some point in 2017. At any given week in that year, some 184,000 people were to be found destitute (less than half of one per cent of the population). In his final report, Alston partially corrects the mistake, writing “1.5 million experienced destitution in 2017”; however, this still leaves it open to the impression that 1.5 million were destitute throughout 2017. Moreover, it omits the conclusion from the same research that destitution fell by 25 per cent between 2015 and 2017.

Admittedly, this decline is hard to believe since nothing tends to fall by that magnitude in comparable social statistics but, nevertheless, Alston is guilty of cherry-picking from that report. He cannot endorse just a selection of its conclusions. Note that 1.5 million in deprivation has become a common claim in political discourse.

Now consider the following claim:

“It may well appear that women, particularly poor women, have been intentionally targeted. It should shock the conscience that since 2011, life expectancy has stalled for women in the most deprived half of English communities, and actually fallen for women in the poorest 20 per cent of the population.”

(My underlining for emphasis)

Claims of a decline for the poorest women are misleading because (1) yearly estimates are subject to a degree of measurement error and differences between years small; and (2) a decline is only evidenced when comparing 2016 with 2011, when estimated life expectancy was particularly high. Taking the figures from the referenced Lancet study, we see for those women in the poorest decile, for example, that life expectancy was 78.8 years in 2016, compared with 79.1 in 2011 and 78.8 in 2010 and 78.9 in 2012.

It would be folly to read too much into these localised variations. The overall trend for the poorest women would be better described as levelling off.

And while the difference in life expectancy between rich and poor is widening, it is categorically wrong to infer causality from such data and certainly below the belt to further infer deliberate design. As the authors of the original study make clear, the causes are complex including selection effects, environmental, behavioural, and dietary factors as well as governmental and economic.

And then we turn to Brexit. Section IX on Brexit in Alston’s final report is just one sentence long and reads:

“If Brexit proceeds, it is likely to have a major adverse impact on the most vulnerable.”

No evidence is offered beyond this simple statement of opinion.

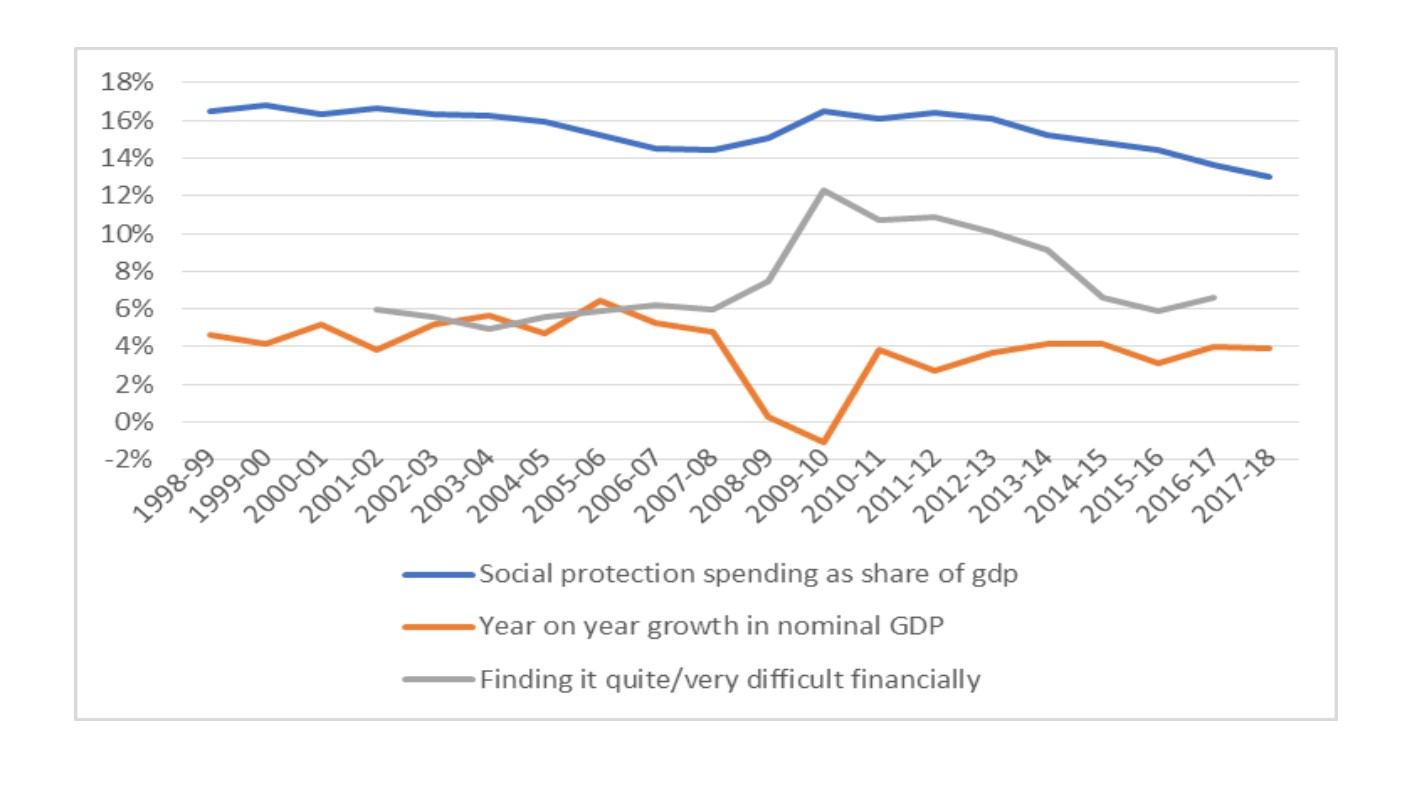

Everything in Alston’s report works back to the conclusion that austerity is to blame for rising poverty. But consider Figure 5 – the Understanding Society surveys’ measure of subjective financial wellbeing stands at just over 6 per cent reporting financially difficulty (2 per cent very/ 4 per cent quite difficult). A far cry from one fifth being in poverty; note how it rises to 12 per cent with the crash but also how it falls as the economy returns to growth, in addition to a reduction in government spending on social protection as a share of GDP, this being a measure of austerity. This doubling in financial difficulty is not picked up by conventional poverty measures.

Figure 5. Subjective financial well-being, public spending on social protection and economic growth

All too often, austerity takes pole position in explaining living standards. The facts of a severe economic recession and unemployment are underplayed.

It is still entirely possible that government policies might have made things worse – perhaps the rise in economic hardship might have been ameliorated; observe how in the graph, growth looks somewhat hampered after the crash. It is also equally possible that government policies such as Universal Credit have made the lives of some utterly miserable while not leading to the immiseration of the majority of the poorest. Indeed, if anything, that is the case to have been made but Alston simply does not do it. It is also possible for something to go wrong while other things go right – a rise in homelessness for some, as pointed out by Alston, may also coincide with a general improvement in economic fortunes. (And note that the evidence would suggest we may thankfully be beginning to turn the tide on homelessness.)

But despite the recession, austerity, and our Brexit shambles, it does appear that living standards are on the whole returning back to pre-crash resting levels. Note that nearly all of the ONS indicators of national well-being are moving in the right direction; a far cry from Alston’s talk of social contracts unravelling and his bleak, preposterous warnings of life becoming “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.