The dangers of a more rigid labour market

SUGGESTED

The flexibility of the labour market, and its consequent ability to generate a variety of new jobs in all shapes and sizes, is what has given the UK an unemployment rate half that of the European average and some of the highest employment rates for women, for young people and ethnic minorities in the EU.

It arguably has a downside: the ability to create jobs at the bottom end of the skill hierarchy is associated with lower average productivity than some of our neighbours, where low-productivity workers are squeezed out of employment by high social security taxes and excessive job protection laws. And the dynamism of the jobs market means that old jobs disappear rapidly to make space for new ones: it is much easier for British employers to dismiss workers than in France or Italy. This can be disruptive for individuals and their families, and we may not have the right mix of incentives for retraining and encouraging geographical and occupational mobility – both geographical and occupational (where excessive government licensing arrangements are often dysfunctional).

But against this, twenty years of employment regulation under New Labour and successive Conservative administrations have improved working conditions for the great majority of employees out of all recognition compared with the glory days of union power to which Mr Corbyn and the TUC clearly look back with fondness. Unfair dismissal rules, anti-discrimination legislation, parental and carer leave, working time regulations, activist health and safety policy, minimum wage laws and a host of other interventions have dramatically changed the employment landscape. Some of this may arguably have tipped the balance too far against job creation, but its negative impact has been muted while the benefits to employees far exceed those ‘won’ by militant trade union action in the 1960s and 1970s.

The workforce itself has changed: skill levels have hugely improved, graduates dominate most new types of job and self-employment has boomed. Employee lifestyles are increasingly individualistic, career-oriented and very different from those of largely manual or craft workers in the heavily-unionised manufacturing and extractive industries of the past.

The plans outlined at the TUC annual conference include the return of collective bargaining on a sectoral level, a repeal of much of the anti-strike legislation undertaken by the Thatcher and Major administrations, new rights for unions to enter workplaces, a higher National Living Wage to be extended to all aged 16 and over, banning of unpaid internships and zero-hours contracts, and the creation of an expensive new Ministry of Employment Rights and an inspectorate.

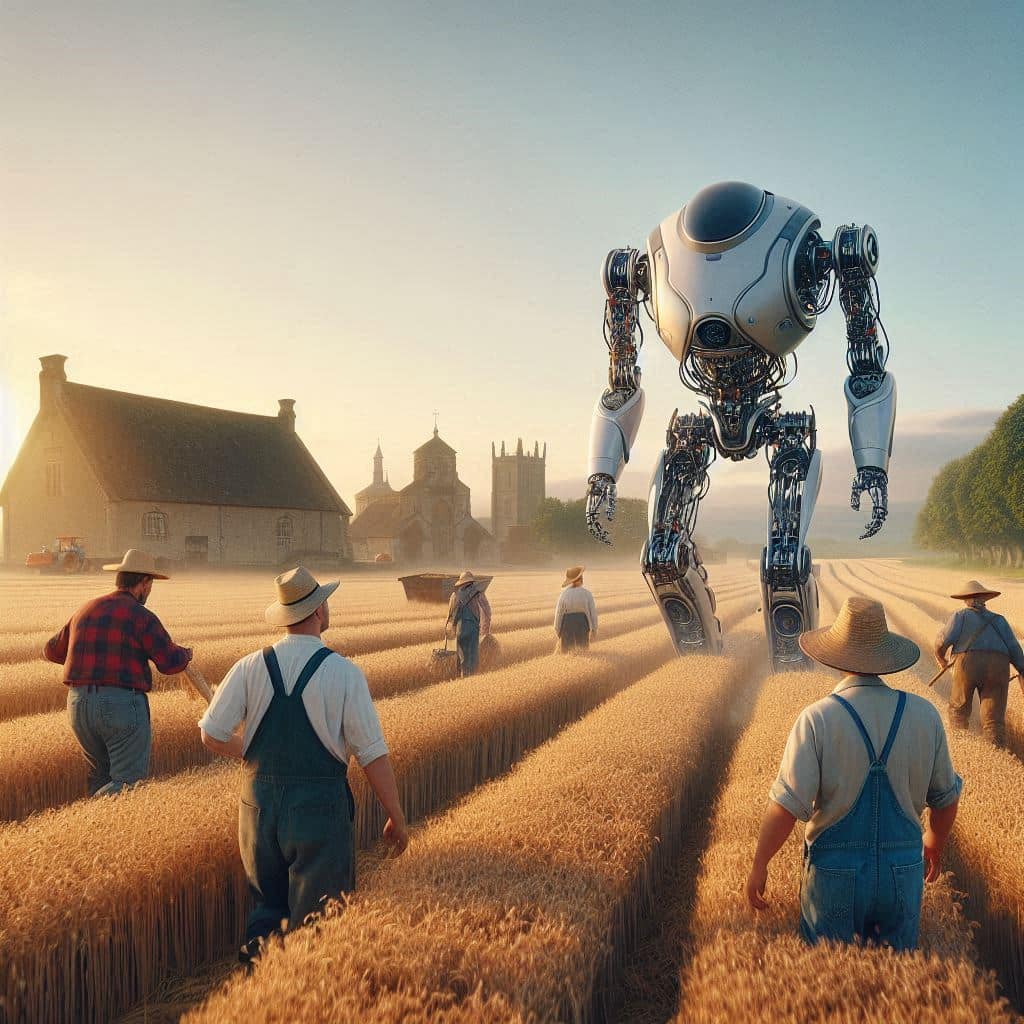

These plans, coupled with previously announced proposals to impose worker representatives on company boards and to renationalise major utilities, will make the UK an unattractive place to do business, as it was in the 1970s. However, whereas 5% of UK shares were held by foreign nationals in 1975, over 50% are today; and capital is much more mobile than in pre-Thatcher days when there were still exchange controls. There is a real danger of some businesses just shutting shop and moving abroad. At the very least, inward investment is likely to suffer. Those companies persisting in operating in the UK will seek to minimise direct employment, outsourcing to businesses elsewhere, and will tend to substitute capital equipment for employees wherever possible.

They will inevitably be more choosy about whom they employ, particularly at entry level where young and inexperienced workers will find it increasingly difficult to access jobs. Trade unions, which are now largely made up of older workers (16-24-year-olds constitute less than 5% of union membership), will focus on protecting existing jobs rather than the creation of new ones. This is likely to push youth unemployment up to the levels in continental Europe.

In 1979, when union membership was at its peak, the UK lost 29.5 million working days to strikes. Last year it was 300,000 – in a much larger workforce. The prospect of a return to large-scale industrial disputes is one which must worry us. Increased strike activity is likely to disrupt large sectors of the economy, rather than simply particular enterprises. This was certainly the case in the 1970s, where “sympathy strikes” were common. Strikes in industries such as railways and the energy sector used to be particularly problematic, as their knock-on effects spread widely. The fact that these businesses are on the nationalisation shopping list is particularly concerning.

A potential incoming government always has policies which threaten disruption, but which in practice are abandoned, watered-down or turn out to be less dramatic in their impact than critics fear. However the Labour Party’s policies in the area of employment law seem more worrying than most. Lower productivity and much higher unemployment seem likely to follow if rigidity replaces flexibility and politics overrides economics.