Can game theory help to explain the UK’s current Brexit difficulties?

SUGGESTED

Game theory became literal “box-office” after the release of A Beautiful Mind in 2001, a film based loosely on the life and work of behavioural economist John Nash, architect of the Nash Equilibrium (NE), a central concept in the theory. The NE is a state in which no participant in a non-cooperative game can improve their position by unilaterally changing their strategy, if the strategies of the others remain unchanged – or more simply, why people making deals often rationally choose second best, or worst-case outcomes.

In a simplified game, each participant normally has two or more possible strategies, and assesses the payoff to themselves against each other possible outcome. The payoff might be cash-related, or something more value-driven, such as political risk or personal acceptability. What is important though is that the payoff measure reflects the relative value the decision-maker applies to each possible outcome, such that they can rationally choose between them.

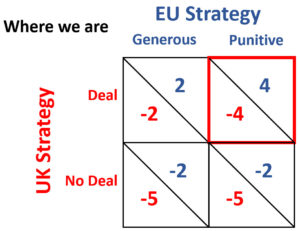

In the context of Brexit negotiations, the equilibrium position became the prime minister’s agreed, then rejected deal. Game theory explains this if we simplify the EU decision towards being generous or punitive, and the UK decision towards deal or no deal. The payoffs in this are subjective. The stated £39 billion cost of the Withdrawal Agreement, for example, is broadly known, but the related trade benefits are speculative and contested. The net payoff then depends on whose scenarios you prefer, Treasury forecasts, Economists for Britain, or others. To make life easier, the parties’ public statements are taken as a basis for assuming their calculations of the relative worth of each payoff. You can pick your own numbers if you disagree. This piece is about how economics can help explain what’s happening rather than supporting any outcome.

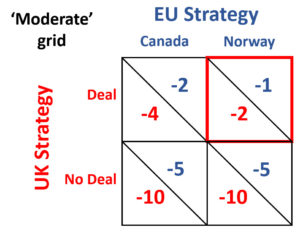

If the assumptions are accurate (Figure 1), the Brexit game was always going to resolve to a “punitive deal”. The EU sees greater value in punishing the UK to discourage others from leaving (4 > 2). The UK sees greater value in any deal versus no deal (-2 or -4 > -5). The government calls this outcome “a good deal”, although by implication of the negative numbers has sold it as worse than EU membership. Many appear to disagree, not least Parliament (twice), which disagreed by the largest majority (230 votes) in modern history, then the fourth largest. Are they not as rational and wise as economic theory might hope them to be?

Figure 1: The UK-EU deal game

Possibly, but if we return to the earlier point that payoff calculations are not financial, but relative utility calculations then it will certainly be the case that different factions are using different calculations. They may then be playing entirely different games.

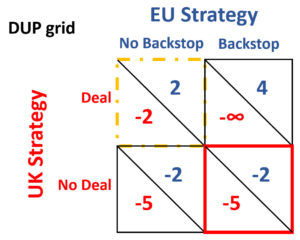

For example, the ten MPs of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), upon whom the government relies for its majority, care most of all about remaining part of and governed by the UK. They owe their electoral success to being resolute, displacing compromising rivals (the UUP) by opposing the Good Friday Agreement. Their grid (Figure 2) is clear. The Irish backstop, a device that if triggered could split the UK, will never be accepted, so the payoff is infinitely negative to the DUP. If they can block it, they will. The equilibrium position in the DUP game is no deal, although with co-operation from the UK government and EU, they would get their optimal outcome, a deal with no backstop.

Figure 2: The DUP game

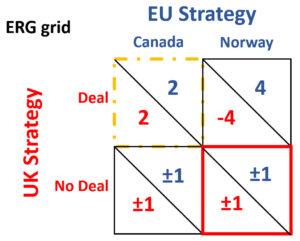

An even larger group in Parliament are the “proper” Eurosceptics (Figure 3) at some 100-150 MPs, principally comprised of Conservative backbenchers (with the European Research Group at the core). They do not have a unitary view on what kind of Brexit they want, but they do want “Brexit to mean Brexit”, which means leaving the major institutions of the EU such as the Single Market, Customs Union, and authority of the European Court of Justice.

Figure 3: The ERG game

Their assessment of payoffs is very different to that of the government. All tend to believe exit under WTO terms (no deal) is either positive, not so bad, equally bad for each party, worse for the EU, or regardless of payoff is an essential check on the EU not to behave unreasonably in negotiations.

They look at the question of a deal principally through the EU’s opening offer at the start of negotiations, Canada (a basic Free Trade Agreement) or Norway (close alignment under EU rules and authority). May’s deal is seen as a form of Norway (although not by all). Where the DUP is implacably opposed to the backstop, the ERG are hostile to rule-taking, which means the ERG game can only resolve to no deal unless both the UK government and EU are prepared to shift towards them, in which case it must be Canada, or one of the many Canada-like options that don’t involve EU authority in the UK.

The main thing that changes the ERG grid payoffs and explains the shift of many between the first and second “meaningful” votes, towards the prime minister, is fear of even more rule-taking or not leaving at all.

Of those who would prefer the government did not shift towards the ERG, up to 80 self-declared “moderates” (Figure 4) apply different values to Canada, Norway and the WTO. Their view, similar to that of the CBI and other multinational business interests, sees all forms of Brexit as worse than staying in the EU. But they would accept a Norway option, either because they believe it’s the best route to rejoining the EU in the future, or that it causes the least cost to employers in their constituencies. Multinationals in turn may see little risk in UK rule-taking, as they can exert influence from other countries such as France and Germany, something unavailable to UK-only firms.

Figure 4: The “moderate” game

If “moderates” were dominant in Parliament, and the government keen, it’s fairly clear they could cut a deal with the EU. A Norway-style outcome is equilibrium for all parties in that dynamic.

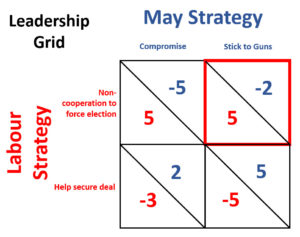

It is though constrained by the payoff calculations of the party leaders, which include what it might mean for their electoral prospects or party unity. In no small part because it would require them to co-operate with one another, which is politically costly – something we can also represent with a game (Figure 5). In this, the prime minister is always better off “sticking to her guns” or working with her own party. Jeremy Corbyn is always better off refusing to co-operate, in the hope it will force a general election. In politics, she has been playing survival, while he has been playing the game of thrones not the game of trade. The actual outcome of Brexit is almost incidental to those internal calculations. And this would certainly explain the odd position of the Labour Party, apparently open to compromise, just not yet, and not with the prime minister or other “moderates”.

Figure 5: The leadership game

Many Labour members conversely want a replay, a second referendum on the original question – this on the assumption that such a vote could happen quickly and would be won by Remain. But the strong suggestion of the previous five games is that no majority can be found for seeking this outcome in the current Parliament. It requires the government payroll and Opposition leadership to co-operate (game 5 says not), or alternatively the Opposition, “moderates” and all the minor parties to achieve sufficient strength to overcome the government, ERG and DUP – something that is being tested, but again doesn’t speak to political payoffs for the Labour leadership. They would lose public support in Leave areas and empower their own “moderates” to lead a national campaign, a wing they are keen to keep marginalised, having only seized the party from them in 2015.

It is more politically plausible that a second referendum would occur after the UK has left the EU, after the impact of leaving is clear (rather than hypothetical), and after a general election, with different leaders, where a party specifically ran with this policy as a manifesto commitment. This would be a “Return”, not “Remain” campaign, calling for an Article 49 process for accession.

On this model (Figure 6) there’s a new issue. The UK will be leaving the EU in 2019 with what other member states regard as an already generous special deal. It has a rebate worth billions each year, and opt outs from the single currency, Charter of Fundamental Rights and some areas of justice and home affairs policies.

Figure 6: The return game

The overall EU position, as with the deal just negotiated, is both a UK-EU game, but also one containing 27 sub-games between the EU and each member state, some of which are entirely relaxed about the UK’s pending absence from the EU, or would only accept the UK rejoining on terms no more generous than their own. Game theory would strongly suggest then that any future deal will not be as privileged as the UK’s current terms. This risk would certainly explain why current Remainers are keener to revoke Article 50 now, however bad the politics of using Parliamentary devices to overturn the public vote, rather than risk the easier politics, but harder outcome plausible from a future referendum.

In conclusion, game theory can certainly help explain a lot of decisions that are currently being taken, or rather being avoided. Membership of the EU has always been both a political and economic question, with many parties to the decisions taken, many complexities in their calculations of payoffs, and to that extent a high risk of sub-optimal outcomes. It seems hard to imagine non-politicians, given a remit to maximise the economic benefit of future trade links would have arrived at anything like the UK-EU outcome, pitching various bad deals against no deal and against usurping a public vote.

Can game theory predict which of those outcomes is going to happen? Only to the same extent as any other forecasting model – results depend on the assumptions made. I’ve made several, which would tend to suggest either the clock runs down to no deal, or the ERG changes their mind, or Labour does, or something happens that fundamentally changes the Parliamentary maths. But other assumptions would yield different outcomes. Which prove to be correct should be clear very soon.

1 thought on “Can game theory help to explain the UK’s current Brexit difficulties?”

Comments are closed.

Thank you for a very clear demonstration of the goals and pay offs in these negotiations.

I note there is no time element accounted for. The options were the same on day one as on day 1,009. So was all the summitry meant to fool us, or to fool the politicians themselves? One might argue that these outcomes only came into focus as negotiations progressed, but surely a good negotiator should game the possible outcomes in advance.

Also, your excellent essay makes no distinction between the EU and the member states. But different countries have different priorities. Some, with a good trading relationship and security arrangements, would want to offer a generous deal, some don’t care much either way and some consider the integrity of the EU a top priority. Some countries (I’m looking at Ireland) have played a very poor hand in this respect. One last question. How did the EU persuade 27 countries that it alone was competent to set the terms of any deal?