What are the chances of a UK/India trade deal?

SUGGESTED

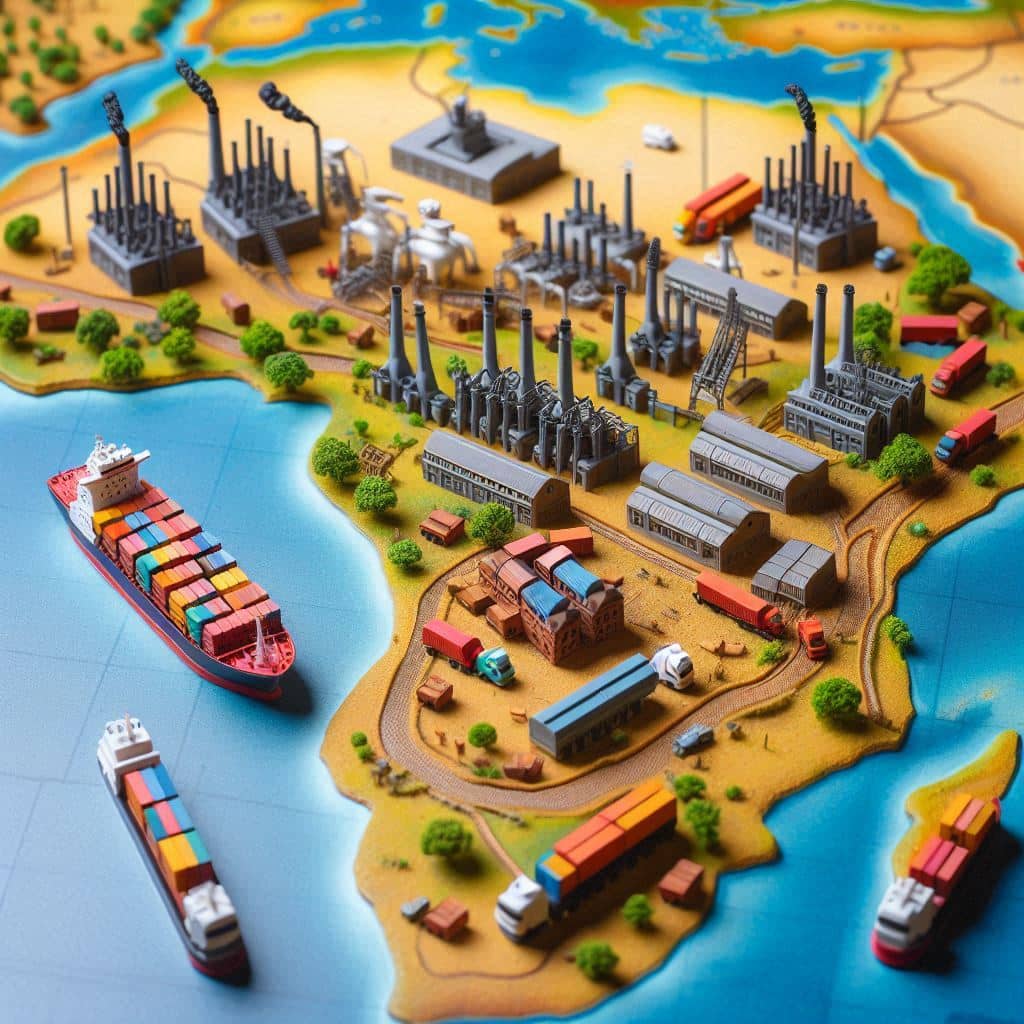

These positive changes derive from an explicit embrace of economic freedom. In 1991, after forty years of socialist policies, India’s government decided to follow the path of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, the result of which was explosive growth (the last quarter of the financial year 2017-18 saw GDP growth of 7.7%). With a population of 1.3 billion, India offers a huge potential market for goods and services.

On the other side of the world, March 29 next year will bring a renewed independence to the UK’s shores – albeit of a rather different kind – as we officially exit the European Union. Brexit could allow free trade deals with some of the world’s largest markets, including the USA, China and of course India, the country once labelled the “Jewel in the Crown” of the British Empire.

Potential and Problems

As of 2016, the UK exports goods worth £3.7 billion to India, and services worth £2 billion, making India the UK’s 13th largest goods export market, and 13th largest services export market outside of the EU. According to the UK-India Business Council, there is great potential for growth in goods like food and drink (including alcohol, despite major tariff obstacles on the Indian side), pharmaceuticals, and robotic technology.

It is hoped that recent digitisation and financial literacy drives from the Modi government will also help encourage UK exports. These include a Smart Cities initiative, which aims to regenerate chosen cities with new technologies, including Water ATMs and the “Internet of Things”. Under Modi’s “Jan Dhan Yojana” programme, 310 million new FinTech bank accounts have been opened, while state-sponsored schemes have also promoted cybersecurity and other digital technologies.

The government has sought to encourage the growth of high-quality, private universities, and there could be an opportunity for British institutions to join in such exercises as well. The University of Nottingham already has a campus in Ningbo, China. It could have one in Nagpur as well!

It may prove more difficult, however, for foreign investors to reap the benefits of India’s growing financial sector. In India, financial services firms can be broadly classified as regulated or unregulated firms. The former are overseen by bodies like the Reserve Bank of India or the Securities and Exchange Board of India. Foreign investors can own 100% of regulated financial services firms (except for banks and insurance companies), without requiring government approval.

For other regulated entities, such as private sector banks, pension funds and insurance companies, ownership (without government approval) is limited to 49%. For private sector banks, ownership can still be as high as 74%, but this requires government approval. For unregulated financial services, like venture capital firms, foreign ownership can be as high as 100%, and does not require government approval. However, their minimum capital requirements can be as high as $20 million.

Reading all that might have given you a headache. The situation reeks of red tape, despite efforts made in recent years, something that could make City honchos think twice before trying to open up shop in Mumbai.

Things look tricky on the legal side too. In March, India’s Supreme Court ruled that foreign lawyers and law firms cannot practice in India on a permanent basis (although they can visit the country off-and-on to advise India-based clients, and can arbitrate in matters of international commercial dispute). This will prove controversial, and a missed opportunity. The Indian “common law” legal system is based on England’s, and its judicial system abounds with unresolved cases, with over a million cases pending in the High Courts for over ten years. Yet British law firms remain unable to realise a huge opportunity.

In bilateral negotiations with the UK, India would almost certainly push for more visas for its skilled labour force. Yet, given the contentious nature of immigration as a political topic in the UK, it seems unlikely that British lawmakers would agree to this. In a post-Brexit world, where free movement between the EU and the UK would diminish, some concessions may be possible, but they are far from guaranteed.

What has been done so far?

In April, the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi visited the UK, and came away with a bilateral agreement which could serve as the foundation of a UK-India trade deal. The deal covers a variety of fields, ranging from technology sharing to animal husbandry. Though it acknowledges that the UK cannot sign any new deals till the end of the Brexit transition period, it does give out some positive signals.

The ‘Chequers’ model may also prove an obstacle to bilateral agreement with the UK, preventing Britain from diverging from EU rules and regulations after Brexit. In practice, India may prefer to focus on reaching a deal with the EU27. Discussions in April reportedly led to “substantial progress”, and the bloc, as a whole, remains India’s number one trading partner – although the EU’s stringent regulations may continue to prevent a deal from being signed.

Clearly, the UK must take a more relaxed stance than its European counterparts if it wishes to leapfrog the EU to a trade deal with India. John Smith from Edinburgh could then enjoy his curry with proper basmati rice, while his counterpart in Delhi samples some of Scotland’s finest whisky.

At present, however, good economics is being trumped by short-termist law-making and decision-taking. Let’s hope that this does not last long.

General Intern