The wealthy aren’t all that bad

SUGGESTED

In times of economic adversity, wealth taxes on the richest are often proffered as a solution. Last week, Labour’s largest union backer, Unite, demanded a wealth tax on the top 1% in order to give public sector workers a pay increase, claiming it was time for a raid on ‘the super-rich’.

After the Government offerred a 22% pay deal to junior doctors and a 15% pay rise to Aslef train drivers, it is clear that handouts will have to be paid through an increase of tax receipts and not further borrowing. This is a problem, particularly when you consider that other unions have continued to push Labour for ‘pay restoration’ that would award above-inflation pay rises to public sector workers. A tax on the wealthiest could be the least politically damaging option for a government that’s growing increasingly unpopular.

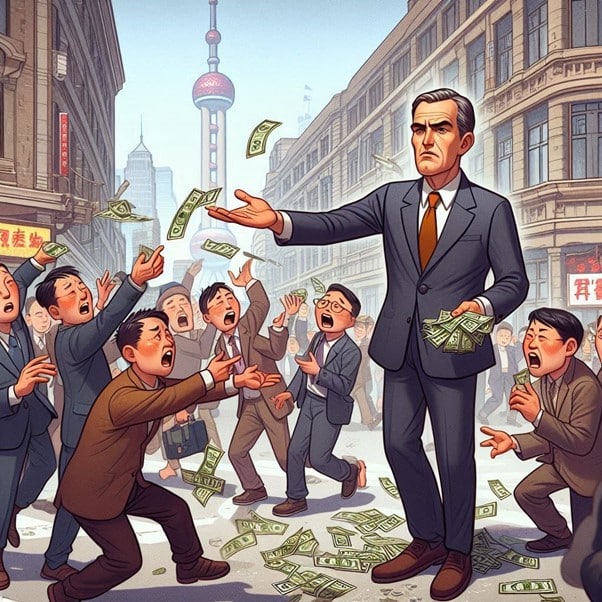

Groups such as Patriotic Millionaires consistently lobby for wealth levies to solve society’s ills, believing that the state should confiscate a higher proportion of affluent individuals’ resources. Like many populist policies, wealth taxes are depressingly popular. Yet history shows that they are unlikely to deliver the results backers might hope for.

François Mitterand, the French socialist president, introduced a wealth tax in 1982, which lasted until 2017 (briefly stopped for three years under Jaques Chirac). The tax was imposed on all those with a net worth of over 1.3 million euros, but only accounted for a grand total of 2% of tax receipts during the period. Some 60,000 millionaires left France between 2000 and 2016 with estimates suggesting that the implementation of the wealth tax cost France double what had been received through the levy. President Emmanuel Macron finally abolished the tax in an attempt to unleash business-friendly policies aimed at attracting investors and revitalising the economy.

Further examples from Europe show similar trends. In 1990, 12 countries had wealth taxes. Today, there are just three. Reports from the OECD suggest that wealth taxes create problems for people who are asset-rich but not income-rich, and whose wealth is tied up in illiquid assets. This would be a serious issue in Britain if a wealth tax were to include property wealth. Almost anyone who owns a property in London would automatically be deemed an asset millionaire, even in some cases if the property was a one-bedroom studio flat.

Taxing income and consumption is relatively simple. Analysing wealth is far more difficult due to the challenge of producing a modern-day Domesday book – a record of who owns what. This doesn’t currently exist, and even if it did, would change constantly.

A further argument against wealth taxes is that they are a form of double taxation. Wealth is usually built up out of income, which is then used to build up assets. This, in essence, discourages savings as a means to avoid such taxes would be to simply spend all earned money at once.

Although Britain does not currently have a wealth tax, we do have a very progressive tax system, which already relies very heavily on the richest – ‘the rich’ in the sense of the highest earners, who need not be those with the highest asset wealth. A little under 30% of income tax receipts come from just the top 1% of the highest earners. That is more than the combined total of the next 20m taxpayers.

Despite popular opinion suggesting otherwise, many of the wealthiest taxpayers are more than happy to pay their fair share. The Coates family, the owner of online sports-betting giants Bet365, have consistently been in and around the top of the list of the UK’s biggest taxpayers. In the 2024 Times Tax List, the Coates family contributed a staggering £375.9m. While most UK sports-betting operators have located their headquarters to more tax-friendly jurisdictions, Bet365 has remained in the UK, in Stoke-on-Trent, where it is a major employer to local people.

Unite should recognise the enormous contribution the wealthiest make to society instead of attempting to leech further off those who already prop up the public sector. Campaigners ought to recognise that millionaires who believe they have a duty to pay more tax already can. Voluntary payments can be made via direct bank transfer to HM Treasury. The fact that this amount each year is minimal suggests that maybe the tax rate is already a tad high.

Our tax system should not be designed to be ravenous. The UK already has a crippling 70-year high tax burden. We are also suffering a long-term period of stagnation and excessive state spending, leading to debt levels imminently approaching 100% of GDP. If the Government wishes to appease public sector workers making unreasonable pay demands or fill the reported £22 billion ‘black hole’, a wealth tax is certainly not the solution.

This article was originally published on CapX.