The government’s “Inclusive Britain” report: the good, the bad, and the ugly

SUGGESTED

What I particularly liked, as an economist, was that the Report recognised that social and economic phenomena have multi-causal explanations. Simple assertions about white privilege and prejudice could not explain disparities such as Black African pupils doing better in education than white pupils, and much better than Black Caribbean students. They couldn’t explain why people of Indian or Chinese heritage earn more on average than white workers, or why black mothers and their babies are more likely to die in and around childbirth, yet black people generally have greater life expectancy than white people.

Sewell and his colleagues attracted considerable hostility for their analysis, with accusations of whitewashing the experience of ethnic minorities. Given this hostility, it might have been tempting for the government to quietly forget the Commission’s Report. To their credit, they have not done so.

The Minister for Equalities, Kemi Badenoch, has this week published Inclusive Britain, the government’s reply to the Commission. The document endorses the general tenor of the Report and offers a point-by-point response to the Sewell recommendations.

Some points are sensible and will inform future analysis; abandoning the use by government statisticians of the catch-all (and widely resented) BAME category in favour of more granular identities is welcome, for example. There are intelligent suggestions for handling drug users and for improved handling of stop and search in the face of continuing knife crime in our cities.

The government has also picked up on the important point made by the Commission – that many ethnic disadvantages seem to be associated with ‘socio-economic and geographic factors’. Clusters of particular ethnic groups in areas where jobs are scarce and poorly-paid explain a significant part of the pattern of disadvantage, and policies to address them should be seen in the context of the government’s wider ‘levelling-up’ ambition.

Some Commission recommendations are fudged. For example, Sewell recommended lengthening the school day to give school students more extracurricular options (and incidentally keeping them off the streets), but the government just churns out some platitudes about increased school funding. And despite the warnings Sewell and others have given about attempts to measure companies’ ethnic pay gaps, it looks as though the government remains sympathetic to the idea. It is going to produce ‘guidance’ for firms which wish to monitor pay gaps voluntarily. While we should perhaps be grateful that the government has not gone for compulsion, as Theresa May wanted, it would have been better to kill this idea off permanently – together with gender pay gap monitoring, which has achieved little but at considerable cost.

There are some extra proposals which are not responses to the Commission, and two are welcome. One is to try to tackle the thorny issue of adoption, where social workers’ understandable wish to place children with families of the same ethnic heritage has come up against a persistent shortage of potential adoptive parents from some communities – leading to disproportionate numbers of black children remaining in state care, with all the baleful consequences which follow.

The other is to take up another point made by economists when analysing ethnic employment outcomes – the differences between immigrant and native-born workers, and the often-ignored contrast in types of immigrants. Black Caribbean immigrants, for example, are younger and less-qualified than black African immigrants.

One Inclusive Britain proposal which has attracted attention has been the government’s plan to encourage inclusion by producing a Model History Curriculum that ‘will stand as an exemplar for a knowledge-rich, coherent approach to the teaching of history’.

I have little enthusiasm for state curricula in general. We managed without a National Curriculum until that talented busybody Ken Baker introduced one in 1988, and I’m not sure it has been a force for good.

I also fear that a curriculum ‘to tell the multiple, nuanced stories of the contributions made by different groups that have made this country the one it is today’, written by ‘history curriculum experts, historians and school leaders’, will do little to reverse the drift of negativity towards Britain’s history and institutions.

For instance the National Museum Wales hit the headlines this week by tenuously linking the 1804 steam engine developed by the great inventor Richard Trevethick to ‘colonialism and racism’. We also heard a mea culpa from the Royal Society of Chemistry, decrying ‘pervasive’ racism in the field of chemistry.

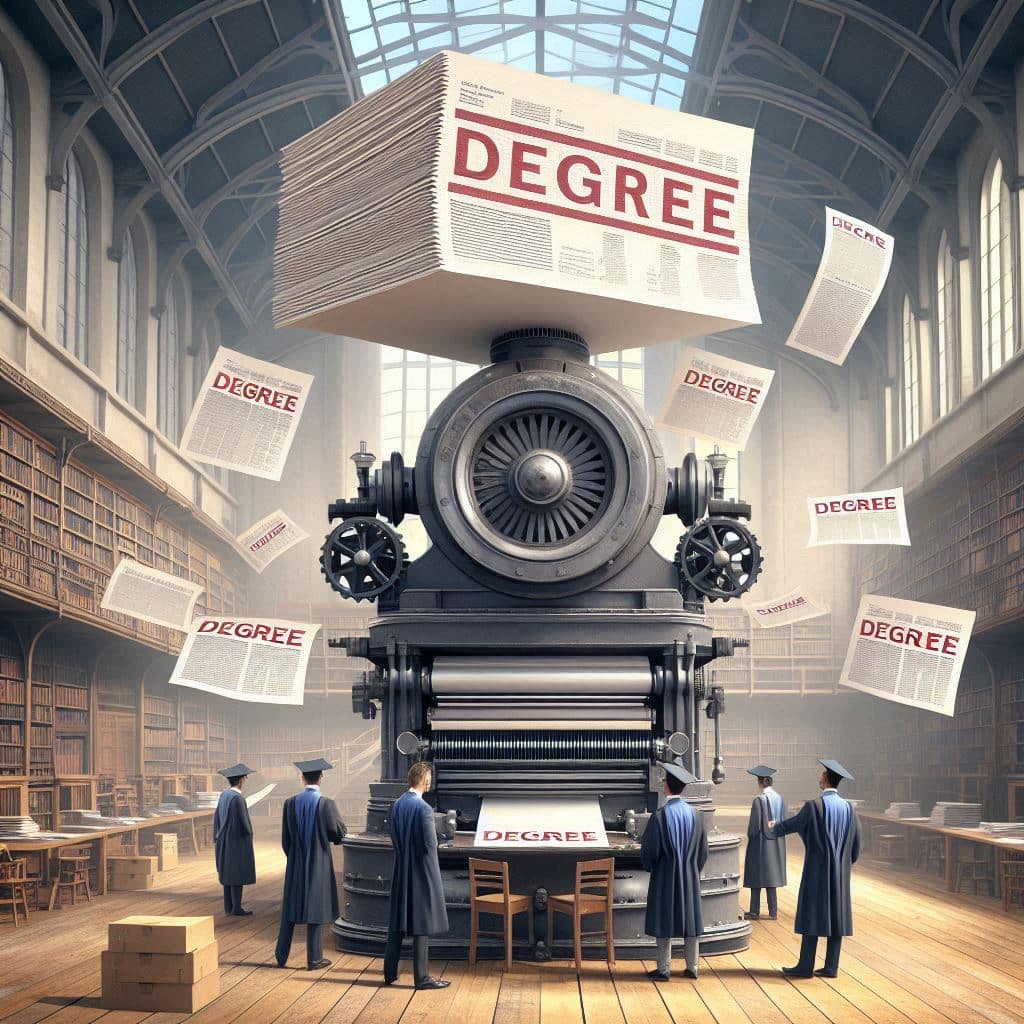

Those who take this sort of line find the more optimistic view of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities – and the current government – difficult to accept. This is why Tony Sewell has had the offer of an honorary degree from Nottingham University withdrawn, According to the University, his views are the subject of ‘political controversy’ – something which today’s universities wish to avoid, apparently.

Against this sort of mindset, the government – despite being the most ethnically diverse to date – will continue to struggle for support.