An Introduction to Taxation

SUGGESTED

Contents

Introduction

The role of this book

This book is not specifically about any specific tax system, but is about the general idea of taxation. It explains what taxation is, why it exists, its history, its aims and purposes, its impact on individuals and the economy, its social and moral results, who pays it, what benefits it has, what damage it does, and how to make it work better.

The book is jargon-free. It is aimed at lay readers who want to understand the role of taxation in society and the arguments around it, and at school and university students who are looking for a broader view of taxation than they can find in their textbooks.

Why this book is necessary

Economic textbooks are remarkably thin on the concept of taxation. They examine it only as a tool for managing the economy, redistributing resources or changing people’s behaviour (e.g. to encourage them to reduce their pollution). But this is far from the whole story.

In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, the pioneering Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723–90) formulated the principles of good tax policy as fairness, certainty, convenience and efficiency – ideals that are widely accepted today (Butler 2007). But, sadly, today’s tax systems often fall short of fairness, being skewed for political purposes and often weighing most heavily on the least well-off. Certainty should mean that people know clearly how much tax they pay, but the complexity of many tax systems makes that impossible. Convenience is about making taxes easy to pay; but again, tax complexity often forces people to hire expensive professionals to guide them. Efficiency means that taxes should be easy to collect and should not distort or stifle commerce, though some taxes almost certainly cause more economic damage than they raise in revenue.

Despite these shortcomings, the textbooks take taxation as a given. They see taxes as a necessary source of funds for the provision of essential and beneficial government services. They explore their workings largely in terms of who pays them and who is affected by them. But they do not explain how and why taxes are created or abandoned, nor how politics affects them, nor what they really mean to people. They rarely ask whether some taxes do more harm than good, or which taxes are most useful or most damaging, or whether there are other ways of funding public services.

Nor do they raise any questions about the morality of how taxes are raised and what they are spent on. This book takes a much broader view, asking these and many other questions in order that we might put taxation and its benefits much more into its economic and human context.

It argues that taxation often falls short of its aims. It explores the principles that would define a better and simpler tax system and examines other techniques that might be used to fund public services with less taxation.

The History of Taxation

The US statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) famously wrote that ‘in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes’ (though modern-day wits complain that the two come in the wrong order). Certainly, taxes have been with us for a long time.

The ancient and medieval world

Governments throughout history have turned to taxation in order to fund their provision of goods and services to the public (or to keep their rulers in a style that reflected and magnified their status). And for most of that history, taxes have centred on the main industry, namely agriculture: the production of the essentials we need to eat and drink.1

Egypt. Between two and five thousand years ago, Ancient Egypt’s Pharaohs employed scribes in their thousands to assess harvests for tax purposes. Grains, livestock, beer and other produce were taxed, with harsh penalties for evasion. The Pharaohs had a monopoly on cooking oil and taxed it, too: officials would enter people’s homes and punish anyone trying to escape the cost by reusing oil.

China. Imperial China was another largely agrarian economy and was taxed accordingly. Local officials were charged with raising set amounts of revenue – though they had discretion about exactly how. The main revenue sources were land and produce, but at various times there would be taxes on salt, artisan industries, valuable metals, tea, tobacco and other goods. This provided finance for the army, public works (including the Great Wall) and other imperial expenses.

Greece. Much tax collection in Ancient and Classical Greece (700–323 bce) was contracted out to ‘tax farmers’, who bid for state contracts to collect taxes. Tax was levied on products, including the all-important olive oil, and on trade (including high tariffs on oil imports, designed to protect domestic producers). There was a poll tax on foreigners living in Greece, and, during emergencies, the richest citizens too were taxed directly (Kolasa-Sikiaridi 2022).

India. Before 300 bce, ancient India also levied taxes on agriculture and trade, and on various professions. There were charges on land, alcohol, salt, mining and other activities. As in Greece, taxes and loans were raised to deal with emergencies.

Rome. The Roman Republic (509–27 bce) levied customs duties on foreign trade, and a wealth tax on land and property. Our word tax may come from the Roman taxare, meaning ‘to estimate value’. Tax farmers gathered revenue effectively, but corruptly, which made the system unpopular. Later, the emperor Augustus (63 bce–14 ce) introduced wealth and poll taxes for all adults. An interesting oddity later in the Empire was a tax on urine collected from public toilets – a valuable source of ammonia to clean and whiten woollen fabric.

England. Another interesting tax was Anglo-Saxon England’s Dane-geld (991–1016), a land tax levied to pay protection money to Viking raiders, to stop them pillaging land and property. Sadly, the attacks continued: in the words of a much later poet, Rudyard Kipling, ‘once you have paid him the Dane-geld, you never get rid of the Dane’. Nor, it seems, was it easy to get rid of the tax: when the Viking threat was eventually overcome, kings continued to levy it.

Local lords could raise revenue too – there is a legend (certainly untrue or exaggerated) that the eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon countess Lady Godiva rode naked through the streets of Coventry to protest her husband’s oppressive taxes on his tenants. But England’s new rulers after the Norman invasion of 1066 were much more systematic; they assessed and recorded the country’s tax potential in the Domesday Book and imposed taxes on fertile land, livestock, townships and much else.

Capitation (or ‘poll’) taxes were levied in England from 1275 onwards. That of 1381, a minimum four pence tax on everyone, is blamed for the Peasants’ Revolt uprising of that year. It was not the first backlash against unfair taxation. After the Norman ruler King John (1166–1216) exploited taxpayers to fund wars abroad, the barons listed their objections to his arbitrary rule in Magna Carta (1215), (Butler 2015). Nor would it be the last such uprising: further arbitrary taxation under Charles I (1600–49) helped precipitate civil wars, and eventually Charles’s execution.

The post-industrial world

United Kingdom. The Industrial Revolution, originating around 1760 in Great Britain, also revolutionised how taxes could be raised. The balance of taxation began to tilt from land, livestock and produce towards business, manufactures, employment and income.

From 1789 to 1831, tax on tallow for candles made artificial light expensive, leading to the expression: ‘The game’s not worth the candle.’ And one of the reasons why wigs declined in popularity in the early nineteenth century was the 1795 tax on the aromatic powders that people dusted them with.

Income taxes go back to ancient times, but their modern version dates from 1799, when the British Prime Minister William Pitt (1759–1806) introduced one to finance the war against Napoleon (1769–1821). His new measure taxed annual incomes over £60 on a graduated scale, from 1 per cent up to 10 per cent on incomes of £200 or more. The tax was generally accepted as the price of victory – though the Parliamentary Commissioner did complain about the number of Members of Parliament declaring their incomes at £59 (Phillips 1967)!

In 1816, with the threat from Napoleon over, the income tax was repealed, and the records burned. But in 1842 Prime Minister Robert Peel (1788–1850) resurrected the tax; though it was supposedly a ‘temporary’ measure, there has been an income tax in Britain ever since. Prime Minister William Gladstone (1809–98) proposed to abolish the tax, but his plans were scuppered by the cost of the Crimean War of 1853–56.

The twentieth century brought higher income tax rates on investment returns, a new ‘supertax’ on the highest earners (collected directly from employers under a ‘Pay As You Earn’ scheme), and new sorts of taxes on company profits and capital gains. The early years of the twenty-first century brought ‘stealth’ taxes on air travel, and on pension funds and other investments.

United States. From the 1660s onward, Britain enacted various measures to stop its American colonists trading with other countries, or to tax their exports if they did. America’s molasses, iron, salt, alcohol, sugar, paper, lead, glass, paint and even hats all came to be taxed by the colonial power. The Stamp Act (1765) imposed a duty on legal documents, newspapers, playing cards, dice and other items. Taxes on tea triggered the Boston Tea Party (1773), and within three years, the colonists would declare their independence and (successfully) take up arms against Britain.

The new country’s government now had to raise its own revenue. Some 90 per cent would come from tariffs on trade, thanks to James Madison’s (1751–1836) 1789 Tariff Act, which put a duty on trade tonnage, and there were taxes on whiskey, carriages, and other luxuries, too. However, the government soon saw tariffs as a way of protecting domestic producers as well as raising revenue, and protectionist duties were imposed on imports of goods such as iron, cotton and hemp.

During the American Civil War (1861–65) the Union government scrambled to raise money, imposing taxes on more items, including luxuries such as gambling, tobacco and alcohol, plus professional services, patents, stamps, manufactures and company earnings. After the war, many tariffs and taxes remained in place. Income tax was ended in 1872, but revived in 1894 – only to be ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court a year later. However, it was not yet dead. In the early 1900s, it re-emerged in a different form, and was raised sharply to help pay for World War I (1914–18).

After that war, there was pressure to ease taxes, and in the 1920s, President Calvin Coolidge (1872–1933) slashed the top income tax rate. Surprisingly for some observers, this led to top earners contributing a larger share, as the disincentive effects of high taxes faded. In the following decades, World War II (1939–45), the Korean War (1950–53), and the Vietnam War (1955–75) all led to tax increases. By the early 1960s there was again pressure to cut taxes, and when President John F. Kennedy (1917–63) cut top income tax rates, the share of revenue coming from higher earners rose, just as it had under Coolidge. The same effect followed the later top-rate tax cuts of presidents Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) after 1980 and George W. Bush (1946–) in 2001–03 (Grecu 2004: 6–9).

Some lessons from history

The historical record demonstrates the ingenuity of governments in finding new things to tax – land, livestock, salt, olive oil, tea, tobacco, candlewax, wig-powder, soap, incomes, profits, urine, paint, air travel, stamps, playing cards, hats and more. In 1705, the Russian emperor Peter the Great even placed a tax on beards. This, however, was not driven by a need to raise revenue: rather, as part of his plan to turn Russia into a leading European power, he wanted Russian men to emulate the clean-shaven fashion of Western Europe. It was an early example of a tax designed to change people’s behaviour.2

Also, it seems, taxes can remain in place long after their original justification has disappeared. Dane-geld outlived the Dane threat, income tax outlived Napoleon, and many other ‘emergency’ taxes have similarly lingered. In 1902, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941) of Germany imposed a tax on champagne to fund the Imperial Navy. Though the imperial fleet was scuttled in 1919, the champagne tax still exists, generating millions of euros in revenue. Similarly, in 1936 the US state of Pennsylvania placed a tax on alcohol to raise revenue to rebuild Johnstown, which had been devastated by floods. Johnstown was soon rebuilt, but the tax (now 18 per cent) is still in force (Shannon 2017).

Taxation Today

Increasing size. Today, the most elaborate tax systems are found in the more economically advanced countries. And in those countries, the amount of tax levied has grown significantly over the last hundred years.

That is partly because most of these countries now have large and costly welfare states covering social insurance, healthcare, housing and education. With an ageing population and longer life expectancy, these programmes have become costlier because they must now serve more people, with more complex needs, for longer.

But taxation has many purposes beyond the funding of state services. These include redistributing income, stimulating industries, building infrastructure, and changing people’s behaviour. And the more money that governments want to raise for these many purposes, the wider and more ingenious is their search for sources. Unfortunately, this can create complexities that put an additional burden on taxpayers.

A few large taxes. Most governments draw the bulk of their income from a few very large taxes, principally on incomes, sales and social insurance taxes (in the US and UK, for instance, these three taxes produce around three-fifths of all revenue). Taxes on companies, capital and property tend to be the next largest, with other taxes being relatively minor revenue earners (see, for example, Keep 2023).

Opportunities and limits. Economic development, however, increases the opportunities for taxation. It brings a greater diversity of taxable industries, processes, manufactures, buildings, professions, services and transactions compared with agricultural economies. Development also brings more wealth, and in general a more equal distribution of wealth and income (OECD 2011), expanding the scope for taxation (the ‘tax base’) even wider: simply, there are more people who can afford to be taxed.

By the 1980s, the Internal Revenue Service had become the US’s largest single employer, and tax was many households’ largest expense. But then taxpayers in the US and other countries started to revolt. In response, several governments in the 1980s and 1990s lowered headline tax rates. Yet even committed tax-cutting leaders such as Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013) in the UK struggled to reduce their governments’ need for money.

New taxes. Governments soon found innovative ways to fill the gap, with taxes on the new technologies and ‘stealth’ taxes that were less obvious to those paying them. They also resorted much more to borrowing – effectively, shifting the cost of government activities onto future generations.

It was an old idea (see Due and Kay n.d.). In medieval times, the governments of Venice and Genoa borrowed from the newly created banks. In 1692, the British government pledged its alcohol tax receipts as security for a loan of £1 million. French finance ministers borrowed in the seventeenth century and onwards. America’s government borrowed to finance its revolutionary war against Britain.

Canada’s debt began with its confederation in 1867. Japan’s government issued bonds in 1870. Nevertheless, government borrowing was generally small, other than in times of war. Then, from the early 2000s, with the rising cost of welfare, pensions and other government services, plus the cost of a financial crash and a pandemic, borrowing rose considerably. That left governments with a big challenge to find more tax revenues to rebalance their books – and to do so without stifling economic recovery.

Types of Taxation

Direct taxes

Taxes are broadly categorised into direct taxes or indirect taxes.

A direct tax is one that a person or organisation (such as a company) pays directly to the tax authorities. Examples are taxes on income, dividends, capital gains, land, property, inheritance and wealth. These taxes cannot be passed on to others: payment is the responsibility of the particular person or organisation.

Proportional and progressive income taxes. In general, direct taxes are designed to reflect the taxpayer’s ability to pay. Higher earners, for example, will pay more income tax than those on lower earnings.

This will be true even under a proportional (or ‘flat’) tax where everyone (or everyone earning above some minimum ‘threshold’) pays the same marginal rate (i.e. the same percentage tax on each additional dollar they earn). So, both low and high earners might pay the same 10 per cent on each additional (‘marginal’) dollar they earn. But while the rate is equal for both, the higher earner will end up contributing a higher total in tax, simply because they are paying the 10 per cent tax on more dollars.

Many jurisdictions, though, impose progressive taxes on incomes. That means the more people earn, the higher the marginal rate of tax they pay on each additional dollar they earn. Thus, someone on a low income might be charged 10 per cent on each dollar of earnings above the threshold; someone on average income might be charged 20 per cent; and a high earner might be charged 30 per cent on each extra dollar earned. Under a progressive system such as this, the top earners pay very much more in total tax. In the UK and US, for example, the highest-earning 1 per cent of taxpayers contribute over a third of national income tax revenues (Delestre et al. 2022; York 2023).

Basing taxation on the ability to pay is one of the key principles of most tax systems. But critics of progressive tax rates argue that they significantly reduce higher earners’ work incentives, which depresses economic activity and therefore general prosperity, and that they encourage unproductive avoidance and evasion.

Taxation according to income is the most effective instrument yet devised to obtain just contribution from those best able to bear it and to avoid placing onerous burdens upon the mass of our people.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945)

Among the other direct taxes, a corporation tax may be levied on companies’ earnings. Property taxes may be charged on the value (or rentable value) of land or buildings. Inheritance taxes are paid (by those who inherit) on the estate of a deceased person. And there may be gift taxes on wealth transferred to other people during a person’s lifetime.

Flat rate direct taxes. Some direct taxes, however, are not based on people’s ability to pay. Vehicle licences, for example, may be levied at a flat rate, or be based on the size of the vehicle, rather than on the owner’s wealth or income.

Another interesting example is poll tax, a uniform charge on each individual. Though arguably a logical way to pay for services that people use roughly equally (such as rubbish collection), poll taxes have generally been unpopular (as in the Peasants’ Revolt) because of the greater relative burden they impose on the least well off.

Indirect taxes

Indirect taxes are not levied directly on a person or organisation. They are remitted to the authorities by one person or organisation, but then passed on to others who ultimately pay them, usually in the form of higher prices. An example is excise duties on fuel, alcohol and tobacco, and tariffs on imported goods. These are all remitted to the authorities by producers, merchants and retailers even before the goods reach the customer. But they are passed on to customers, wholly or partly, in the price of the goods they buy. Similarly, a sales tax is collected and remitted by the retailer when goods are sold, but it is ultimately paid by customers.

(Although employers sometimes deduct social insurance contributions and income tax from employees’ pay, these remain direct taxes, since they are taxes on the individual employee, even if, for convenience of collection, they are collected and remitted to the authorities by the employer.)

Varieties. Consumption taxes are indirect taxes that may take the form of a general sales tax (GST) on consumer products, or a value added tax (VAT) that taxes the product at each stage of its manufacture. Sales taxes are another example. These may be charged at a flat rate on the price of whatever the customer buys, though sometimes ‘luxuries’ (such as prepared meals consumed in a restaurant) are taxed at higher rates than ‘essentials’ (such as raw food bought in a supermarket).

Sales taxes are generally ad valorem taxes. That is, they are levied at a certain percentage of the price of goods and services. The more expensive the product, therefore, the more tax is paid. Another form of consumption tax is excise duties. But these are specific taxes: i.e. they are levied on each unit quantity of the particular goods and services, not on their price. Thus, the same excise duty is payable on a bottle of wine, whether it is the finest Château Mouton-Rothschild or the cheapest supermarket blend.

Purposes. Indirect taxes have many purposes other than raising revenue. Excise duties, for example, may be used to raise the price of (and thereby, reduce the demand for) goods that are regarded as harmful – harmful either to the individual (e.g. alcohol, tobacco and gambling, with their possibilities of addiction) or to others (e.g. fossil fuels, with their environmental impact).

Scale. Indirect taxes constitute a large proportion of the total tax revenue raised by the governments of many countries. In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, they comprise around a third of the tax take (OECD 2022). That proportion has been rising, partly because economists today regard consumption taxes as less damaging than taxes on incomes and corporations.

Regressive nature. However, critics argue that indirect taxes are regressive. Specific taxes such as excise duties form a higher proportion of the price of the cheap products bought by poorer families than of the price of the expensive ones bought by the rich. Tariffs, likewise, raise the price of imported goods for every end customer, regardless of their means. In addition, some of the main targets for import tariffs are typically essentials such as food and clothing: since these already absorb a larger part of poorer households’ budgets, the extra tax falls most heavily on those least able to afford it.

A tax on sales, goods and services or value added again raises the price of food, clothing, fuel, housing, transport and other essentials, hitting poor families hardest. This is why many consumption taxes are levied at different rates (e.g. as mentioned, on ‘essentials’ or ‘luxuries’) to offset this regressive effect. Unfortunately, this then increases the complexity of the tax, making it more arbitrary and harder to enforce. In the UK, for example, the zero rate of VAT on children’s clothes, determined by their size, means that small adults can buy tax-free clothing while the families of large children have to pay the tax. And the UK government faced ridicule when a cold pie bought in a shop (classed as an ‘essential’) bore no tax, but a warmed-up one bought from a takeaway (classed as a ‘luxury’) did (Quinn 2012).

Covert nature. Critics also complain that indirect taxes are hard for taxpayers to see. Someone buying an imported car, for example – and even the retailer it is bought from – is probably unaware of how much tax has been paid on it in the form of tariffs and excise duties. Shops may not even itemise the sales tax on the price tickets of their goods. And, say critics, a key principle of taxation is that taxes should be known and transparent.

Potential politicisation. Both direct and indirect taxes can be used to favour certain industries and activities over others. However, it is more common to use indirect taxes for this purpose because their less visible nature helps conceal the preferential treatment.

Thus, a government that wants to boost employment, say, might levy lower consumption taxes on the products of labour-intensive industries (e.g. agriculture, catering and services), while raising those on capital-intensive products such as cars, telecommunications and energy. But critics point out that this distorts the normal working of the economy, drawing resources into sectors that may deliver less value to consumers. Worse, the tax may be used politically to help a government’s own supporters: a government with a strong base in rural areas, for example, may choose to lower taxes on rural industries for the benefit of its voters there.

Transfer taxes

A transfer tax is one levied on the transfer of ownership or title to property from one person or organisation to another. In a sense, sales taxes are a sort of transfer tax, because any sale of goods is a transfer of property. But in general, the term is reserved for the transfer of property that must be formally registered or declared in some way, such as land, buildings, shares or bonds. Examples include stamp duties on the transfer of land or securities, inheritance taxes paid on the transfer of a person’s estate after death, or gift taxes paid on transfers to friends and family made during life. The rate payable is normally based on the value and type of the property.

Direct or indirect? There has been debate about whether transfer taxes should be regarded as direct or indirect taxes. In Knowlton v. Moore (1900), the Supreme Court of the United States heard a case in which a taxpayer argued that Estate Tax was a direct tax on the inheritors, rather than an indirect tax on the estate. (Since the tax was graduated, calculating it as a tax on the total value of the estate would produce a larger tax bill than calculating it as a tax on the smaller amounts inherited by each beneficiary.)

The Court ruled that Estate Tax was an indirect tax on the transfer of property rather than a tax on property itself.

Tobin taxes. Some people advocate transfer taxes not only on the exchange of physical goods but also on financial transactions too – a financial transactions tax (FTT). The British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) thought such a tax would calm speculative bubbles (such as 1920s Wall Street) by making it costlier to buy and sell assets. This, he reasoned, would discourage high-volume buying and selling in the speculative hope of making short-term gains, while sales and purchases that focused on securing long-term value would remain relatively unaffected (Burman et al. 2016).

In a 1972 lecture, the American Nobel Prize economist James Tobin (1918–2002) proposed a similar tax (or ‘Tobin Tax’ as FTTs have come to be known) on currency conversions, aiming to protect the 1944 Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates from speculative runs on weak currencies.3 This purpose is now redundant, given that today’s floating exchange rates adjust automatically to market realities. More recently, in 2011, the European Union (EU) has promoted an EU-wide FTT on all financial transactions as a way of generating revenue for the (supranational) European Commission and reducing its dependency on EU member governments.4

Critics. The different forms of transfer tax each have their critics. Some complain that inheritance tax, for instance, hits people at the worst possible time – after the death of a close friend or relative. They see it as contrary to the natural human instinct of providing for one’s family. They note that people will go to great lengths to avoid it – setting up complicated trusts or switching their fortunes into lower taxed but perhaps less productive assets. They say that if people could invest freely instead of being driven to such measures, it would benefit them and the wider economy much more (see, for example, Bracewell-Milnes 1995b).

Taxes on land and property transfers, continue the critics, make moving home more costly. So, older people, whose families have left home, then remain in houses that are too large for them, rather than downsizing and freeing up the space for a family that needs it. Such market inertia also leaves people trapped in homes that are far from their work, increasing travel time, costs and pollution. And the tax encourages evasion – for example, sellers agree a lower price for the taxable property, but an inflated price for fittings, furniture, garden ornaments or other untaxed items.5

And FTTs, say critics, ignore the fact that speculation has benefits. Speculators usually have the sharpest knowledge of individual markets and whether prices in them are too high or too low. So, their buying and selling activity speeds up the adjustment to current realities, boosting the efficiency of markets and thus the productivity of the whole economy. Even if the tax on each transaction is small, imposing it on the millions of financial transactions that occur every day still amounts to a major distortion of economic activity.

Hypothecation

A hypothecated tax is one where the revenue raised by the tax is ‘earmarked’ or ‘ring-fenced’ for a particular purpose, rather than going into the government’s general funds. Some of the licence fees already mentioned may count as examples. A historical example is ship money, a tax levied on English ports in the seventeenth century, and used to finance Britain’s Royal Navy. More modern examples include social insurance taxes, which are used to provide services such as pensions and healthcare; vehicle and fuel taxes that go to the upkeep of the roads; and airport taxes that are used to maintain airport facilities.

The degree of hypothecation can be strong or weak. Strong hypothecation is where the revenue raised goes only to the nominated service, or the service is financed only by the tax. This is appropriate for services such as social insurance for healthcare or pensions, where most of the benefit is enjoyed by the paying individual. Weak hypothecation is where the revenue does not all go to the nominated service, or where the service is funded additionally in other ways. This might be appropriate where there is a wider public interest, such as education.

Criticism. Hypothecated taxes have obvious benefits. If people know that what they pay will indeed go to the nominated service, and will not be used for other purposes, hypothecated taxes may attract more public support and trust than general taxation.

But can the public really be so sure? For example, social insurance taxes might not be ring-fenced for social insurance purposes but may in reality be no different from income tax, both going into the government’s general funds. Yet it may serve politicians to claim they are separate because it makes the tax on income look smaller. There is also the question of what people get for their hypothecated tax. Is it spent widely (in the case of education, say, on the whole range of nurseries, schools, colleges and adult education) or narrowly (where it funds, say, only schools)?

In general, we would expect people to support strong and narrow hypothecation, where the revenue goes only to the specific service. However, it is not always clear whether or not that is the case.

Another criticism is that public spending on any particular service should be determined by the need for it, not the amount of money that can be raised from it. Moreover, many taxes will raise more revenue when commerce is expanding and incomes are rising, but it is during the times of economic recession and rising unemployment that government services such as social insurance are most needed.

And tax revenues might not match need, nor expenditure, more generally. Motoring taxes, for example, may raise many times the amount spent on road maintenance, or can be justified by environmental damage (see, for example, Ebbs 2014). Nor do we expect tobacco taxes to be spent only on treating the associated health problems of smokers. They can and often do raise far more than is needed for those services. While politicians might like to suggest that taxes are largely hypothecated, their real interest is in keeping the revenues as free to spend as possible.

Purposes and Problems

The main purpose of taxation is to raise revenue to finance the services provided by a government, such as defence, the justice system, roads, education, welfare, pensions and healthcare. But it is used for other purposes, too. For example, a government might try to regulate the economy and smooth boom–bust cycles by raising taxes during upturns and cutting them during downturns. Or it might aim to reduce inequality by raising taxes on wealthier people and reducing them for others. And it might hope to reduce the demand for harmful products such as alcohol, tobacco and leaded fuel by putting taxes on them.

Sometimes, though, governments use taxation for less noble purposes. For example, taxes may be skewed on or off particular groups (such as property owners) with the aim of benefiting supporters of the ruling party. Or they might be used to benefit favoured domestic producers by taxing lower-priced imports. They might even be imposed on successful groups out of envy, or on ethnic or religious minorities out of antipathy.

Why taxes?

The prime duty of any government, for which they seek to raise funding from taxation, is to establish peace and security: to protect its citizens against hostility from abroad and criminality at home, making life and liberty feasible (see, for example, Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes, 1651). That means standing up against the threat or use of force from foreign powers, and protecting citizens against intimidation, deception, fraud or violence from their fellow citizens. This is not a small task, nor a cheap one, as it requires the building of substantial institutions.

For example, the pursuit of peace and security implies the existence of national defence, security, police and justice systems. It means having a military that can deliver a credibly effective response to any attack. It means having a police service that can provide a deterrent against crime and investigate and prosecute crimes when they occur. And it means having a system of courts and punishments.

It might even imply the existence of a regulatory system to ensure that all these agencies operate in the public interest and are not corrupted. There must also be an institution, such as a parliament, to decide on what actions count as hostile or criminal; how the defence, policing and justice systems should operate; and what punishments are appropriate when crimes are committed. And perhaps a civil service is needed to administer all these functions. All of this needs to be funded, just for government to discharge this one basic function.

The free rider problem. Most people can see the benefit of having defence and security: but would everyone pay towards it voluntarily? As long as enough people paid to ensure that the country and the community was well protected, the others could enjoy the benefits of that protection even if they paid nothing. Under those circumstances, it might be hard to get anyone to contribute, knowing that they could ‘free ride’ on others who do.

The normal solution to this problem is to compel everyone to pay for these services, under threat of punishment for non-compliance. In other words, to levy a tax on citizens.

This is not a wholly comfortable option. The use of force against citizens is precisely what government is there to minimise. And some people may have moral objections against their money being taken to spend on armaments, say, or against the policing of laws they regard as unjust, or against imprisoning people. Yet there remains wide agreement that taxation, at least for these basic protection purposes, is justified.

What range of services?

More controversial is the question of what institutions and services are so necessary, and so impossible to fund in other ways, that they must be paid for through taxation.

No clear boundary. Even Adam Smith, though a critic of big government, believed that the state had a role in the provision of infrastructure such as bridges and harbours. These, he reasoned, are vital to the trade and commerce that enriches society, though they could never deliver a profit to any individual provider. The state had a role in providing schools and adult education, too, he thought, since these are important to culture and the mental health of workers and their families (Butler 2007).

But there seems to be no logical limit to this. Infrastructure, for instance, might be stretched to include the state provision of transport and utilities. Education might be taken beyond normal schooling to include the state provision of colleges, adult learning programmes and vocational courses, too. Healthcare might be used to justify state provision not just of doctors and hospitals but also of health clubs and even dancing classes. Arguably, such goods and services may all help boost a country’s economic performance. But, critics ask, do they all have to be provided by governments, out of taxation?

Public goods. Governments also provide amenities, such as local and national parks, lighthouses and streetlamps, that are classified as ‘public goods’ because it is hard to prevent anybody accessing their benefits, and many people can enjoy their benefits at once. Here, the argument is that without taxation these things could never exist, because people could ‘free ride’ without paying, and no producer would invest in them.

But the standard lists of what constitute ‘public goods’ seem exaggerated. Often, these goods can indeed be charged for, or otherwise funded, without using taxation. Even lighthouses – long hailed as the purest sort of public good because their warning light is accessible to any passing vessel, even without payment – originated with marine pilots lighting bonfires to advertise their navigation services; for a long time, they were funded by charges on vessels calling into nearby ports (see Geloso 2019).

National parks, too, can be funded by the limited sale of mineral prospecting rights, or by parking and accommodation charges and the sale of food, beverages, souvenirs, garden plants and much else.6 Shopping malls provide customers with public goods such as light, heating, security, seating and toilets, not by charging them directly for each one but by charging their commercial tenants for the ‘bundled’ package of facilities. Volunteer groups keep clean parks, beaches and other facilities. And new technologies allow providers to exclude free riders – such as scrambling cable and satellite television signals or identifying and charging motorists who use congested roads.

To conclude, though taxation may well be an obvious way of funding many goods and services, and may be unavoidable, there are many other possibilities that should be considered but are often overlooked.

Taxation for public investment

As Adam Smith noted, it might not be in the interests of private individuals to fund some physical investment (e.g. infrastructure such as communications, transport or buildings) or human investment (e.g. education, skills, knowledge and R&D) – despite the fact that investment in such items would benefit the whole community. Consequently, it seems that government-led investment in these projects is important, necessary and inescapable.

Nevertheless, government-led investment has its problems. Critics argue that it ‘crowds out’ private investment by absorbing much of the available capital, and that public investment, being driven by politicians and civil servants, is less productive than that driven by value-focused entrepreneurs.

Investment or spending? Another problem is the fluidity of the term ‘public investment’. Economists regard investment as using resources to buy or create goods that will produce other goods or services quicker, better or cheaper, or that will produce a financial return. Thus, when manufacturers spend money on machinery, or people go to night school to earn qualifications that make them eligible for better-paid jobs, or buy bonds to provide their income in retirement, those are investments.

In the public sector, spending money on a new highway or harbour that will speed the transportation of people and goods, or installing airport passport scanners that process arrivals more quickly, or building new school science blocks are all investments.

Spending, by contrast, is using resources for gratification today, not in the hope of future gratification. And in reality, the huge bulk of government expenditure in the developed nations is ‘day to day’ spending on current benefits such as welfare payments, pensions, health and social care, housing, transport and refuse collection. While some of these may have some future benefits, they are all aimed primarily at benefiting us today. Politicians might call them ‘investment’ because that sounds a more worthy use of taxpayers’ money, but this does not make it any more legitimate as a justification for taxation.

Macroeconomic management

Most economists maintain that taxation and government spending have a key role in steering a nation’s economy to full employment, stable prices, economic growth and the avoidance of boom–bust cycles. They argue that governments should expand their spending or cut taxes to stimulate an ailing economy, or should cut spending or raise taxes to combat rising inflation. This so-called demand management approach has played an important role in many nations’ economic life since World War II.

Yet this approach has its critics, too. Some – e.g. monetarists such as Milton Friedman (1912–2006) – argue that other factors such as the amount of money brought into existence by the central bank outweigh the effects of tax changes (see Butler 2011). Others – e.g. public choice school economists such as James Buchanan (1919–2013) – observe that government decision-making is often irrational: for example, politicians gladly raise expenditure in bad times but show great reluctance to cut it in good times, and much prefer to cut taxes than to raise them (see Butler 2012a). Thus demand management theory is overwhelmed by practical politics. And some observers – e.g. Austrian School economists such as F. A. Hayek (1899–1992) – believe that these political realities explain why the post-war decades saw so much inflation, unemployment, government expansion and rising debt (see Butler 2012b).

Redistribution

Another common aim of taxation is to promote economic equality by shifting more of the burden onto those who can most afford it.7 Taxing better-off people more than others is seen as fair because money is of less value to someone who has plenty of it than to someone on the breadline (an example of the general principle of ‘diminishing marginal utility’), so they will not feel its loss through taxation so keenly. Many countries therefore operate ‘progressive’ tax systems whereby those on higher earnings pay higher rates of tax than those on lower earnings.

Issues. Yet there are difficulties about using taxes in this way (Butler 2022). First, the inequality statistics on which the redistribution policy is based can be misleading. A snapshot of society may suggest large inequalities of income and wealth, for example, but much of that may be because the older people, with greater experience and skills, earn more than younger ones – even if each may earn identical amounts over their lifetimes. Second, some people, such as footballers or music stars, may have large earnings, but their careers may be short. Over a lifetime, again, they may be little better off than others. Third, some people earn a lot doing dangerous and unpleasant jobs while others earn less but have easy and enjoyable work: there is more to equality than money alone. And there is more equality than might appear, since many public amenities – parks and open spaces, roads, schools, policing and much else – are accessible to everyone.

There are also political, moral and practical concerns about using taxation in ways that affect some groups more than others. It opens taxation up to the politics of envy – with higher taxes imposed on successful groups merely because others resent their success. The ruling party may skew taxes onto the opposition’s supporters. And powerful interest groups may be able to extract favourable tax treatment, which others cannot. Progressive taxation also treats people differently, contrary to the principle of equality before the law. And in practical terms, progressive taxation soon gets very complicated, as those paying the higher rates lobby for reliefs and exemptions. (Such complexity is one reason why many countries have chosen to replace their progressive taxation with ‘flat tax’ systems in which everyone pays the same rate.)8

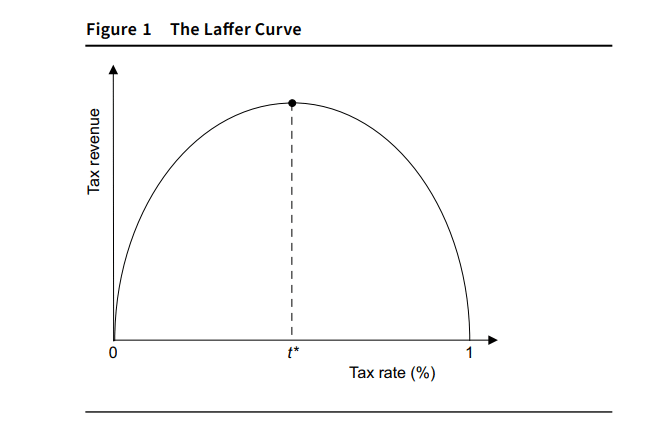

Error, or envy? It is a common assumption that the higher a tax rate is set, the more revenue it will bring in for the government. But in 1974 the American economist Arthur Laffer (1940–) created his famous hump-backed ‘Laffer Curve’, which suggested that receipts rise only up to a certain point, beyond which they start to fall. There are many reasons for this. Faced with very high tax rates, people may decide to work less and take more leisure, or retire earlier, or move themselves or their business abroad (the ‘brain drain’), or employ expensive accountants to find ways around the tax.

Often, though, we find that tax rates, particularly the top income tax rate, are set dangerously close to (and occasionally above) the revenue-maximising point on the Laffer Curve. Higher earners start to contribute a lower proportion of the tax revenue than they did before, while cuts in the higher rate of tax, as mentioned in chapter 1, lead to them contributing a larger share. So, why do legislators set such high rates, given that the main purpose of the tax is to maximise government revenue at minimum cost to economic life?

There are many possibilities. Perhaps policymakers fail to grasp the Laffer argument entirely. Or perhaps they see only the immediate boost to revenues that come from a tax increase, not the gradual decline of revenues as people gradually change their behaviour because of it. Maybe they imagine that the tax will be harder for people to avoid than it really is. Perhaps they understand Laffer’s argument but imagine that the revenue-maximising rate is higher than it is. Or perhaps they wish merely to indulge the public’s envy of higher earners. Whatever the reason, it is clear that taxes are not always imposed in a rational and evidence-based manner.

Tackling negative externalities

Another aim of taxation may be to combat negative externalities such as the effects of air and water pollution on ecosystems, or the delays and frustration caused by road congestion, or the public health costs of excessive alcohol, tobacco and sugar consumption. By taxing such things, we can make those who produce the negative effects pay the whole ‘social cost’ that their actions impose on others. These taxes are called Pigovian taxes, after the British economist Arthur Pigou (1877–1959). They can take many forms, such as road congestion charges and fuel duties, taxes on emissions, a carbon tax, alcohol and tobacco duties and sugar taxes.

Pigovian taxes are a better way to tackle negative externalities than most alternatives. Judicial options, for example, taking polluters to court, are slow and expensive, and happen only after the damage has been done. Regulation is often crude; for example, banning certain noxious emissions outright is harsh on those industries that have no other option, or that produce only manageable amounts of pollution. Limits on pollution levels give no incentive for those below the limit to cut their emissions even further. A tax on emissions, by contrast, induces everyone, across all industries, to reduce all their emissions wherever they can.

Economists favour Pigovian taxes for two other reasons. First, as already mentioned, if well structured, they raise the cost of a person’s or business’s externalities (such as airborne pollution from their activities) up to the costs (such as lung disease) that these impose on others. Second, if individuals and businesses have to pay for the pollution they cause, it will discourage them from doing it, resulting in a general improvement in the environment and in social welfare. For governments, too, they can be a useful source of revenue.

However, Pigovian taxes do face both theoretical and practical problems. The British economist Ronald H. Coase (1910–2013) argued that the critical factor in problems such as pollution is transaction costs – how hard or easy it is for the polluters and those affected by them to reach a deal on the issue – and taxes may be an inefficient option (Coase 1960). Furthermore, there are the calculation and knowledge problems identified by the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) (Butler 2010a). It is very difficult to determine exactly how high the social costs are, and therefore what the right tax level should be. Estimates vary, for example, about how strongly carbon dioxide emissions affect the climate. Setting a Pigovian tax incorrectly might do more harm than good.

Trade management

Another use of taxation is trade policy. Most countries impose taxes – tariffs – on imported goods, often to protect their local producers from foreign competitors. Sometimes, their aim is to make their country self-sufficient, or to give their new industries time to grow large enough to compete with cheaper producers abroad (the ‘infant industry’ argument). They may believe that others are unfairly bringing in goods that are priced cheaply or even below cost (‘dumping’), perhaps with the specific intention of undermining the importing country’s own producers and strengthening their market dominance. Countries may also object to imports from countries that do not share their own high employment or environmental or food standards. Or they may be worried that they are spending more on buying goods from other countries than those others buy from them (the ‘trade gap’).

The infant industry argument was a prominent driver of trade policy in the 1960s and 1970s. Developing countries raised tariffs against imports and created their own manufacturing industries, making steel, cars, domestic appliances, even electronics and aircraft. But the results were disappointing. Often, these industries had no comparative advantage over other producers, and being insulated from the effects of world competition, their products were often expensive and of poor quality.

There are other downsides to taxing imports, too. A country’s trade barriers make its own population worse off because the imported goods that their consumers want (and which their producers need for their production processes) become more expensive or even totally unavailable. Locally produced alternatives might not exist or might be of poor or insufficient quality. In addition, the possibility of getting protection against foreign imports leads other domestic industries to lobby for it, further restricting competition in other markets. And tariffs require a costly bureaucracy to administer. For all these reasons, economists today generally agree that whatever the temporary benefits for a few producers, tariffs and other trade barriers are a mistake (Butler 2021: 63–77).

Why people disagree on taxation

There is a great deal of disagreement about taxation – in particular, what the overall level of taxation should be and how and from where that should be found. Much of this disagreement is due to the different beliefs people have about the nature and efficiency of government.

To some people, government is a largely benevolent agency, which aims to maximise the welfare of the society, and which largely reflects and represents society’s collective preferences. They see taxation, well designed and at the right level, as a potential force for good – a necessary means of funding public services and investment, and having many other useful purposes such as tackling inequality and economic fluctuations. That being so, they maintain that governments should be left free to decide both the overall level of taxation and how it is raised, such as which activities should be taxed more than others.

Other people, though, are less sanguine. They might see government as, at best, both unrepresentative and inept, a bureaucratic leviathan that is riddled with perverse incentives and incapable of delivering what the public wants either cheaply or efficiently. Or at worst, they might regard government as a self-regarding elite of corrupt politicians and lazy officials who claim to serve the public interest but, in reality, pursue only their own. In evidence, they argue that taxation policies are often short-sighted, irrational or counterproductive, and can be a source of considerable economic and social harm.

Not surprisingly, therefore, these critics seek to impose limits on how and how much government may tax us. To see if they are right, it is worth looking at the realities of where taxes fall and what (often unanticipated) economic and social effects they have.

Impact and incidence

The impact of a tax is how it affects the person from whom the tax is collected (for example, whether people fly less in response to a tax on airline trips). This is different from the incidence of the tax, which is about who ultimately pays the tax (for example, the shop customers who ultimately pay the sales tax that is collected by the retailer, because the retailer adds this cost to the price of the products that customers buy).

The impact of taxes

Let us look first at impact. Some taxes are deliberately intended to have an effect on the behaviour of those who face them. As mentioned, taxes on alcohol, tobacco or vehicle emissions may be intended partly to prompt people to drink, smoke or pollute less by making those activities more expensive.

When something is taxed, it becomes more expensive to produce or consume. So less of it is likely to be produced or consumed. A tax on lead in motor fuel, for example, aimed at reducing pollution in vehicle emissions, raises the price of leaded fuels – which prompts motorists to demand, and producers to supply, less leaded fuel and more unleaded fuel. Since taxes like these impose an economy-wide pressure on everyone to use or produce less of the taxed pollutant, they can be very effective: the tax on ozone-depleting chemicals in the US under President George H. W. Bush (1924–2018), for instance, led to a 38 per cent reduction in their use (Hanson and Sandalow 2006).

Too often, though, the impact of taxes is neither intended nor desirable. A tax may be designed solely to raise revenue, and yet may produce social and economic effects that are no part of its designer’s intention. For example, high taxes on imports make smuggling more profitable, requiring the authorities to spend considerable time, effort and money to tackle smuggling in order to protect their revenues. Taxes on tobacco or alcohol, meanwhile, increase the incentive for gangs to produce and supply illicit, untaxed versions of these products – versions that may be far less safe than the legitimate brands – and again drive consumers into the arms of criminals, who may well be prepared to use violence to protect their illegal trade.

Even within the legitimate economy, taxes have unintended and sometimes undesirable impacts. The cost to consumers of a tax on their favourite products, for instance, is not just the sum they pay on the items they consume; it is also the forgone enjoyment of the additional items that they would have consumed in a world without the tax, but now do not because of the higher price.

The work–life balance

But taxes are not restricted to ‘bad’ things, such as pollution, which we want less of. They are also imposed on ‘good’ things, such as productive work and business, which, sadly, we might then get less of, too. Exactly whether that is so, and to what extent, will depend on the interaction of two effects.

Substitution effect. The imposition of a new tax on income or a rise in income tax, for example, changes the way people think about work and leisure. The tax leaves workers with less take-home pay for the same effort. This makes work less attractive to them, and leisure more attractive. So (in what is called a substitution effect), people may opt to do less work and take more leisure. They might work less overtime or fewer hours, or move into part-time work, or even quit working entirely. If they stay in work, they may be less willing to do more than the minimum expected of them. So, less work goes on in the economy, businesses become less productive, and economic output is depressed.

Moreover, because the tax leaves workers with less take-home pay, they may have to cut back on their spending. And because of that falling demand, businesses produce and supply less. Workers might also save less because their daily expenses now eat up a larger proportion of their earnings, leaving less room for saving. But savings are vital in providing the capital for investment; with fewer savings being banked, lenders have less money available to lend to businesses that want to invest in more productive equipment and processes. All this again depresses the country’s output and growth.

Income effect. In some cases, though, there may be a pressure in the opposite direction, known as an income effect. Because income tax leaves people with less take-home pay, some (particularly the poorest) might be prompted to work more hours to make up for the money they have lost in tax.

Wide impact. It is not always easy to predict whether the substitution or the income effect will be greater, though in general the substitution effect is stronger: when you tax something, you tend to get less of it. Exactly what happens will vary according to the particular tax and people’s reactions to it. But the effects can be wide: as already stated, taxes on income from work and on business can affect how much people work, how productive they are at work, how much they save, how much they invest, how much is produced, and how and where it is produced. They can affect how much money governments have available to spend, and the balance of incomes between rich and poor, and more.

How large are the effects? Economists and politicians disagree, however, on just how much people change their behaviour in response to taxes. Some argue that people tend to carry on their own lives without changing anything much merely because taxes go up or down. Others argue that people are very sensitive to tax changes indeed and that even small changes in tax policy can lead to huge – and not always predictable or desirable – changes in people’s activities.

In light of recent debates about the Laffer Curve, tax authorities have gradually shifted their position. In previous decades, many authorities did not factor behavioural changes into their calculations. They assumed that a rise in income tax rates, for example, would, of necessity, bring in increased revenue. Increasingly, however, they have concluded that people do indeed alter their actions in response to higher or lower rates – in the case of income tax rises, perhaps retiring earlier or working less and taking more leisure – and that this in turn might affect economic growth. Such ‘dynamic’ modelling of tax impact is now a normal part of government budgeting in, for instance, the US, the UK and other developed economies.9

Other impacts

Income inequality. Such effects are not always intentional, nor desirable. For instance, progressive income taxes, whereby a higher proportion of the income of higher earners is paid over in tax, may be a deliberate strategy to make take-home pay more equal, and the tax revenue may be used to provide goods and services (e.g. housing, healthcare and education) for the benefit of poorer people, reducing the inequality even further. But then other taxes (particularly those on food, fuel, alcohol and tobacco) are regressive. They have a much larger impact on poorer families, since the cost of these items, including the tax, absorbs a higher proportion of their household budget than of the much larger budgets of wealthy families. So, this pushes economic inequality up again.

It can be difficult, therefore, for policymakers to balance their various objectives. We want to preserve the incentives on good things such as productive work, yet it is easy to tax work in a way that produces more equality in take-home pay. We want to discourage the ‘bads’ such as alcohol, tobacco and emissions, but it is hard to tax these things without hurting the poorest more than others. As with all taxes, we have to ask if the damage they do is worth the benefits they might bring.

Cascading problems. Tax may have other unfortunate consequences. Taxes may force the poorest people in the poorest countries, for example, to cut back on necessities such as nutrition, making them less able to work and contribute economically. Likewise, if taxes discourage work, saving and investment, the resulting fall in productivity hurts the poorest most, since they benefit more than others from being able to buy cheaper, better products, and from having more work opportunities.

Further impact problems

Compliance costs. Another impact on taxpayers, beyond what they actually pay in tax, is what it costs them (not only financially, but in time and effort) to comply with the tax rules. This includes individuals’ and organisations’ time and expense in studying and filling out tax forms, keeping the appropriate records, and preparing and reconciling financial data. It also includes the cost of getting help and advice on these questions, such as the expense of hiring accountants and lawyers.

These costs fall particularly hard on small businesses and self-employed persons, taking up a larger proportion of their time, energy and money. While all businesses have to deal with the various rules on income, payroll, capital and sales taxes, a large company can afford dedicated compliance departments full of knowledgeable tax specialists. But in a very small business, compliance is up to the individual owner, who may not be an expert on tax accounting. By favouring large, established businesses over small, new ones, business taxes can discourage competition and entrepreneurship.10

Deadweight losses. Taxes raise revenues for governments to spend on public services, on the provision of infrastructure, pensions and welfare benefits, and the other purposes outlined in chapter 3. Yet, when governments create new taxes or raise existing ones, the results can be counterproductive, creating a net loss for society, not a gain.

This phenomenon was explained by the British economist Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) (Marshall 1890). By raising taxes on particular goods or services, a government hopes to collect more revenue – and may well do so. But the taxes also raise costs for the producers of those goods or services, causing them to raise their prices. That results in consumers buying less, and producers selling less. Demand and supply are then both lower than everyone’s ideal. This gap between the pre-tax and post-tax production volumes is known as the deadweight loss of the tax. It is a loss to society in general, and not just a financial loss but a loss in terms of the forgone enjoyment that people would have had, in the untaxed world, from consuming more of the products they desire.

These losses can stretch into the very long term. By reducing producers’ returns from their investment, effort and entrepreneurship, the tax lowers people’s incentives to invest, work and take entrepreneurial risks, causing productivity and growth to slow. And it encourages producers to try to avoid the tax, perhaps diverting their investments into projects and processes that are less taxed but may be less productive.

So, even if the new tax produces greater revenue for the government and allows it to provide more tax-funded services, there may well still be a net loss to society as a whole, stretching into the future. Moreover, the fact that total tax revenues may fall as a result of the reduced economic activity makes the possibility of an overall loss even greater.

Unpredictable losses. Ideally, taxes should be designed to deliver the most benefit for the least cost. But because the effects of different taxes cascade through the economy and down the years, the total reduction in production can be hard to assess.

As outlined above, taxes on earnings may mean people switching from work to leisure, work becoming less productive, and economic growth slowing. Taxes on capital, for instance, may see finance, land and equipment being switched from productive (but taxed) uses into less productive (but untaxed) ones. Taxes on rental homes, meanwhile, may prompt owners to leave the market, making rentals scarcer and more expensive, perhaps forcing people to travel further to their work or else take less productive jobs locally. Taxes on investment may reduce people’s willingness to finance new businesses, and taxes on business may increase the (already considerable) risks involved in starting up and growing a business, leading to less job creation, innovation and progress (Butler 2020a: 107–11).

Given how diverse these effects are, and how hard it is to measure them, it should be no surprise if many taxes actually end up producing a net loss to society.

Avoidance and evasion. A special case of deadweight cost is the time, effort and ingenuity that people put into avoiding or evading taxes.

Avoidance is where people use the tax rules, or loopholes in them, to minimise legally the amount of tax they are due to pay – for example, by setting up family trusts to avoid inheritance tax, or taking their income in lower-taxed forms, such as in dividends or benefits in kind, rather than salary. The large size of this deadweight cost is evidenced by the scale of the industries that help people avoid tax – trust lawyers, tax planners and many more.

England’s curious history of tax avoidance

England had a long history of tax avoidance. In 1660, there was a tax on fireplaces. The idea was that people in larger homes, with more fireplaces, would be taxed more than those in smaller ones. But people avoided the tax by bricking up their fireplaces. So, the tax collectors’ attention turned to chimneys, which were easy to count from the outside.

In 1696, a window tax – another proxy for property size – was introduced. In 1797, Prime Minister William Pitt (1759–1806), keen to tilt the tax burden towards those who could best pay, raised the tax substantially, but this led to people bricking up windows to avoid the tax– the health implications of which led to the tax being repealed in 1851.

Another luxury, printed wallpaper, was taxed from 1712. But builders avoided this tax by hanging plain paper and painting patterns on it. Also in the 1700s, when bricks were taxed, builders simply started using bigger bricks, prompting the government to respond with a larger tax on bigger bricks. The tax lingered until 1850.

To avoid a 1784 tax on hats, hatmakers simply called their products by other names. In 1804, the government responded by extending the tax to any form of headwear, but eventually the tax was abolished in 1811.

In contrast to avoidance, evasion is where people illegally conceal or understate their earnings or other taxable activities in order to pay less than is due under the law. They may simply lie on their tax forms, say. Or tradespeople and professionals may ask to be paid in cash rather than declare their receipts for payroll and sales taxes. Meanwhile those in illicit trades – such as (in some countries) sex workers and drug dealers, sellers of fake merchandise, or those smuggling high-duty goods such as cigarettes – are driven to evasion because they cannot declare their earnings openly without revealing their unlawful activities (though curiously, the US Inland Revenue Service demands that they do just that).

“Income tax has made liars of more Americans than golf.”

– US humourist Will Rogers (1878–1935)

Precisely because these activities are undisclosed, it is impossible to measure the scale of what is called the hidden (or shadow) economy. By some estimates, its average size across all nations is around 30 per cent of the declared economy – over 60 per cent in counties such as Bolivia or Zimbabwe, though less than 10 per cent in countries with more efficient tax-collection systems such as Austria, Switzerland and the US (Schneider and Williams 2013; Shenfield 1968).

However, an unfortunate consequence of tax avoidance and evasion is that the authorities’ response to it is almost always to raise costs on honest taxpayers as well as on ingenious avoiders and dishonest evaders. They might impose stricter rules on reporting – making the tax code longer and more complex but, as a result, more difficult for taxpayers to navigate – or they might instigate intrusive inspections into people’s tax affairs, and harsher penalties on those under-reporting, even as an honest mistake.

Conclusion. Taxes, then, can have profound and unexpected effects on the economic and social structure. Economists agree that the best tax policy is one that addresses genuine externalities, preserves incentives to work, save and invest, and promotes productivity and prosperity, with minimal distortion to economic life and without running governments into long-term debt. But these ideals are often far from the practical reality.

Tax incidence: who pays?

The person or organisation from which a tax is collected is not necessarily the person or organisation who ultimately pays it. Shopkeepers facing an increase of sales tax on their goods, for example, might try to pass the extra burden on to their customers in the form of higher prices, rather than absorb it themselves. If they succeed, then the tax is ultimately paid by the customers, even though it is collected by the shop.

Where the burden of taxation ultimately falls (e.g. on shopkeepers or customers) is called the incidence of the tax. Just how far the person collecting the tax (e.g. the shopkeeper) will pass it on to others (e.g. customers) depends upon market conditions – on the income and substitution effects described earlier, on the amount of competition from other sellers, and on how people value the particular goods and services involved.

An example

Suppose that the government imposes a tax of ten cents on books. A bookshop may then try to charge an extra ten cents on each book they sell, rather than pay the tax themselves. The ten-cent higher price, however, may deter customers from buying as many books from that supplier. They might instead decide to read more online, or borrow books from libraries, or read magazines, or travel to cheaper bookshops, rather than pay the increased price. So, the bookshop will find it hard to pass the full ten cents on to customers.

If, however, customers prefer books to magazines, do not like reading online, or cannot access a local library or other nearby bookseller, then the bookshop can pass more, perhaps all, of the tax on to the customers in higher prices.

Likewise, if the bookshop is completely unwilling to sell at lower prices – perhaps because there is intense competition in their market and profit margins are already at the bare minimum needed to survive – the more of the tax will it try to pass on to customers. But if it is content to accept lower prices – perhaps it has a local monopoly, and its prices are already high – the more of the tax it will end up bearing itself.

Who ultimately pays how much of the tax, therefore, depends on market factors, on the willingness of customers to pay more – what economists call the elasticity of demand – and the willingness of sellers to accept less – the elasticity of supply.

Lessons for governments. The important lessons for governments, as they seek to raise revenue from taxes on goods and services, is that the more customers are willing to buy something, even at higher prices (i.e. the more inelastic their demand), the more tax can be extracted from them. Tobacco smokers, for example, often find it difficult to quit, so have little option but to pay the higher prices, which competitive retailers can pass on to them in full.

This is why excise taxes are mostly levied on goods such as tobacco, alcohol and fuel, where demand is inelastic and customers are more willing to put up with high prices. Duties are not usually placed on goods such as magazines, carpets or chessboards, where demand is elastic, because customers’ needs are not critical, and they have easy alternatives.

Incidence of different taxes

Different sorts of taxes on goods and services have different effects on tax incidence – i.e. on who ultimately pays them. Excise duties, for instance, are levied on each unit of the goods traded, regardless of their cost. Typical sales taxes, however, are a percentage of the price of the product. So, people pay more tax on the higher-priced goods.

Excise duties are regressive, therefore, because they do not reflect people’s ability to pay (and perhaps also because dutiable goods such as fuel absorb a larger proportion of the household budgets of poorer families). Sales taxes, by contrast, put more of their burden onto households that can afford to buy more expensive goods (Snowdon 2018a,b).

Analysis of the relationship between impact and incidence reveals other unexpected results. For example, workplace taxes such as social security or national insurance taxes are often described as being paid by employers But they also affect workers by making it more costly for employers to hire people, and perhaps forcing them to reduce staff numbers and offer less attractive conditions. Corporation taxes, too, are supposedly paid by company owners, but several studies suggest that workers bear the greater part of the tax, perhaps even more than it raises.11 One possible reason is that the tax leaves businesses with less money available to invest in productive capital, so workers’ productivity does not increase, and neither, therefore, do their wages.

Economists disagree on such effects. But it seems wise for legislators to give proposals for new or increased taxes the most careful analysis and scrutiny.

Taxes and government

Investment, by individuals and businesses, is essential to future productivity, and therefore to economic growth and progress. Taxes, however, shift resources from individuals and businesses to government, which reduces their scope to invest. But taxation also gives the government more to invest (and spend) on behalf of the community – though in a different way.

Government vs private investment

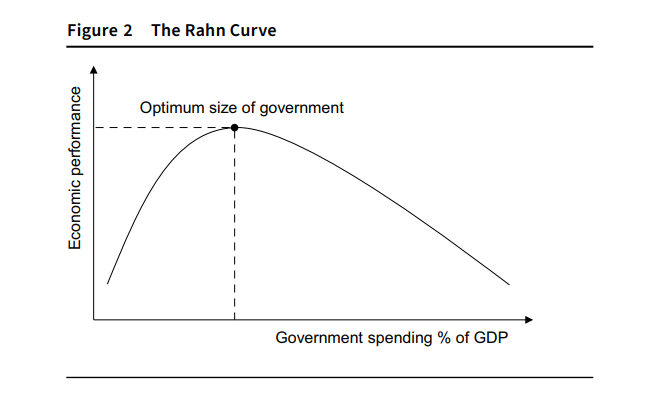

Some economists think that governments will invest more than the private sector because they keep less of their resources in idle savings, and that governments can invest more efficiently because they can undertake large infrastructure and other socially useful projects that are beyond the scope of private individuals and groups. And such investment can boost the effectiveness of private investment, too. Businesses may invest in creating innovative products, but if government builds better road and rail networks, private producers can get more of those products to market, faster and more easily. Supporters of this argument point out that many high-tax countries (e.g. Sweden) are highly developed and rich, while many low-tax ones (e.g. Albania and Afghanistan) are considerably poorer.

Supply-side criticisms. Critics, however, challenge this view. In the first place, they argue, there are many reasons why some countries are rich and others are poor. Sweden might be even richer if it lowered its tax burden. There are also trust differences: Swedes are generally prepared to pay higher taxes than Albanians because they trust their government to spend their money well, while Albanians generally do not. That in turn might explain why, despite a very high tax level, Sweden’s shadow economy is relatively small.

Government spending, say its critics, is still notoriously inefficient. Much is wasted on politically inspired and prestige projects that are of low value, and usually late and over budget. Much of what politicians call ‘investment’ is really only current spending. And with public finances always tight, governments tend to give in to public employees’ wage demands and put off capital maintenance and renewal, leaving the public infrastructure outdated and crumbling, and public services an inefficient drag on growth.

For these reasons, so-called supply-side economists advocate keeping taxes low to encourage private investment and growth. They believe that lower tax rates will boost economic activity by incentivising people to work and invest, while lower tax revenues will prompt governments to invest and spend more efficiently. The result, therefore, is greater productivity and economic growth.12

Supply-siders concede that it may take time for people to adjust their work schedules and plan their new investments, so the higher-growth benefits of supply-side policies may take two or three years to show. In the meantime, the government’s finances may be strained, but this temporary strain, they say, is worth the long-term benefits.

Taxes and politics

As already noted, taxation has many purposes other than financing government spending – such as discouraging harmful activities, creating new infrastructure, boosting equality or promoting industries such as tourism. Many economists are comfortable with this, seeing the government as better than the private sector at steering resources in the national interest.