Office conversion: an opportunity to boost the supply of urban residential housing

SUGGESTED

The 1960s, however, were also to see a revival of the clearance of so-called slums, houses (sometimes owner-occupied, but more usually rented) considered by the authorities as unfit for habitation. Demolition on a large scale of largely Victorian-era dwellings had started during the 1930s and 341,000 of them were cleared by 1938. Then came the War, a cessation of the formal policy but an unintended, randomised replacement by the loss of inner-city housing to Hitler’s Blitz on British cities in 1940-41.

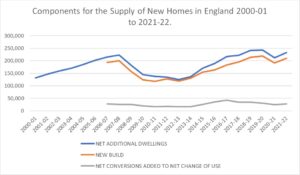

After the War, planned clearance of dilapidated housing was slow to get going again at a time when, with construction materials and labour in short supply, building to make-up for wartime losses of the housing stock took priority. Even so, between the mid-1950s and the end of 1960, local authorities had cleared around a further 260,000 unfit dwellings, reaching 70,000 annual clearances by 1966. Thus, the net addition to the stock of dwellings in the much vaunted peak of the postwar construction boom was significantly less than the magic 300,000 figure, and not a great deal different from the total added during the years immediately preceding Covid. Here lies a crucial point: it is net additions that the debate about housing supply might usefully focus upon, not just an obsession with newly built houses.

Fast forward to this century, what we find is a much reduced number of demolitions, dwindling to an annual total of about five thousand in the last few years. And recently a newish feature of significance: dwellings added through existing buildings changing their use or being converted. Indeed, in England this category accounted for nearly a quarter of total additional net dwellings in 2016-17. Although this proportion has fallen since, ‘change of use’ continues to make a useful contribution to the stock of additional homes.

-ONS, Table 118

An interesting question is whether conversions and change-of-use numbers might be boosted significantly to provide a major source of new homes. Conversions of rural properties, barns, oast-houses and other farm buildings are a familiar event in rural areas. In towns and cities, transformation of offices has featured. Indeed, recently the chief form of urban property conversion has been from redundant offices, and it is in this regard that we might look for a possibly major boost on the dwellings supply-side, particularly in view of the significant change in working patterns and, with it, a revaluation of offices as an asset class for investors.

Working from home is a development that is controversial, but its growth pre-dates Covid (annual rail season ticket sales suggest this). It was, however, Covid lockdowns that provided a major boost for this practice. This has led to an underutilisation of current office space, even in prime areas such as central London, where recent reports suggest local vacancy rates up over 50 per cent on the long term average. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that prime city areas will see much office conversion to residential. The economics do not always stack up. On the other hand, for peripheral areas, the likes of Croydon, Ealing or even Canary Wharf and particularly in towns and provincial cities such as Reading, Leeds or Bristol, the financial balance might well be moving in favour of conversion on a major scale.

To be borne in mind here is an important development in building regulations. New energy efficiency standards for commercial property from 2027 suggest expensive retrofitting of earlier built offices is pending and this might act as a catalyst for conversion to residential. Some office infrastructure might convert easily to residential use, mostly apartments, other buildings less so. Importantly here government might be able to play a part by encouraging local authorities to consider seriously this development opportunity, and even, perish the thought, easing some planning restrictions so that the opportunity is firmly grasped.

3 thoughts on “Office conversion: an opportunity to boost the supply of urban residential housing”

Comments are closed.

OK for smaller office blocks but those with large horizontal cross-sections in both directions will leave the central part of the floor space without natural light or ventilation.

@KJP: Great, that makes it easy to decide where to put cupboards, utility rooms etc.

Is the lovely Centre Point building, offices or residential

Is David related to the charismatic Dr David Starkie?

?