How will Covid-19 affect global trade?

SUGGESTED

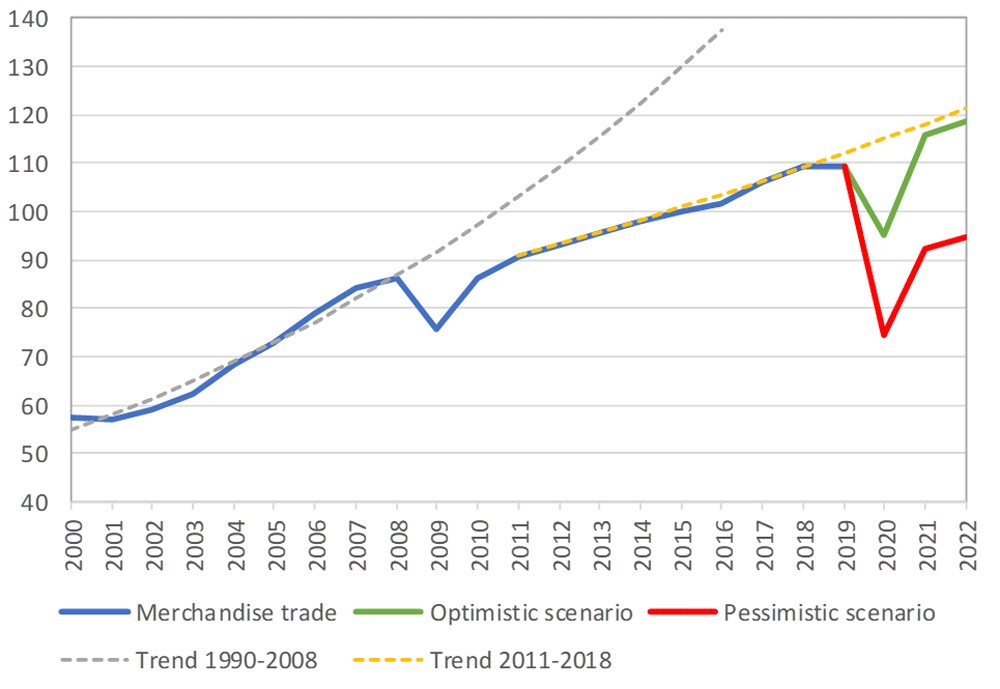

World merchandise trade volume, 2000‑2022 (100 = trade volumes in 2015)

A number of factors could affect the recovery of global trade volumes.

Confidence

A strong rebound in trade is more likely if the pandemic is seen as a short one-time shock and if businesses and consumers quickly resume investment and spending. The rebound will be weaker the longer lockdowns continue or if there are subsequent waves of infection.

Supply chains

The World Economic Forum claims “the coronavirus crisis has revealed the fragility of the modern supply chain”. In response, companies may seek to increase stocks or rely more on domestic suppliers. However, some supply chains have proved remarkably resilient. Once economic activity picks up, not all companies will be able to switch suppliers and many will risk there being no pandemics or major disruption for many years.

Trade tensions

Since his election, US President Donald Trump has renegotiated or withdrawn the US from trade agreements and announced tariff and non-tariff barriers against China and EU countries. His refusal to appoint WTO Appellate Body judges could mean “trade disputes blow up into trade wars”. The EU is also making protectionist noises with a recent headline declaring “Here comes European protectionism”. Trade tensions and slower economic growth led to a 0.1% fall in trade in goods in 2019.

Concerns over the Chinese government

Increasing concerns over the Chinese government’s record on human rights, foreign policy, intellectual property rights, cyber-attacks, technology espionage, currency manipulation and more recently the Covid-19 outbreak could lead to a backlash, affecting trade with China – which accounted for 12% of global trade in 2018.

Technology

According to ING, by 2040 to 2060 3D printing could account for 50% of all manufactured goods, potentially reducing international trade in manufactured goods by between 23% and 40%. While the World Bank believes that 3D printing may not necessarily displace global trade, it has the potential to do so.

Environmental measures

As more countries set environmental targets, there have been calls for trade barriers in the form of carbon border adjustment mechanisms on goods produced in countries with lower environmental standards. Consumers are also demanding more locally produced food, in the belief that it is better for the environment.

Temporary restrictions

In response to Covid-19, eighty countries and customs territories have temporarily restricted exports of medical supplies, medical equipment, food and toilet paper. As Milton Friedman warned in Tyranny of the Status Quo (p. 115), “nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program”.

Reasons for hope

It is not all bad news and there are reasons for optimism. Trade in services increased by 2% in 2019, even though trade in goods fell. A pledge to open trade was signed in April 2020 by 49 countries, representing 63% of global food and agriculture exports and 55% of imports, promising to ensure that Covid-19 restrictions are temporary. Other countries are expected to sign.

The new UK Global Tariff (UKGT) will eliminate several EU tariffs, leading to 60% of UK trade being tariff-free compared with 47% previously. While the EU might become more protectionist, it could equally seek to compete with the UK in securing trade agreements with third countries.

Conclusion

While global trade is expected to recover once lockdowns are lifted, a number of trends evident before the crisis suggest the recovery may be limited. A recent IEA paper on pandemics predicted that “we will almost certainly see a resurgence of protectionism, much re-shoring of production and shortening of supply chains, greater hostility to migration and an emphasis on domestic production of certain kinds of product – particularly food … [T]his is an intensification of a trend that was already under way”. The omens for global trade may not be good.

This blog post is based on a forthcoming IEA Covid-19 Briefing Paper.