Getting out of crises quickly – what do we know?

SUGGESTED

In principle, one might say that politicians and governments ought to react to economic crises in a way that both protects people’s jobs and livelihoods and limits the economic damage, as well as reducing the risk of future crises. That is also the way almost all crisis policy is sold to the public: as necessary interventions to either protect jobs, the entire economy, or government finances. The idea is based on a tradition dating back to Keynes, which claims that crises are a market failure of sorts.

Yet, even if one accepts the premise that government ought to do something, one has to ask the question whether politicians and civil servants in reality are willing and able to do the right thing. This type of question is central to what is known as “robust political economy”, a particular combination of insights from Austrian Economics and the Public Choice School pioneered by, among others, Professor Mark Pennington of King’s College London. These problems are substantial at the best of times, but could become particularly severe in the build-up to economic crises where market information might be less precise than in more normal times.

Governments’ well-known problems of gaining precise and complete information to inform regulatory policy are made worse by the influence of special interests that provide biased information to governments and regulators. The regulations that result from such processes reduce investment and distort the allocation of resources. During crises, extensive market regulation is therefore likely to lead to deeper crises and slower recoveries, because it prevents firms and individuals from reallocating their financial capital, physical equipment and investments – and their labour – to new and potentially profitable purposes.

As originally described by Gordon Tullock, the influence of special interest groups on politics can also deepen crises in another way. Entrepreneurs, who create new products and firms and introduce innovation, are particularly important during the recovery period of a crisis. Existing firms and jobs have been destroyed and both new and existing firms need to soak up unemployed resources. But special interest groups have incentives to lobby government to protect the firms that are most likely to die during a crisis.

As such, two different theoretical traditions within economics reach very different conclusions on policy. In a new paper for the Swedish think tank Timbro, I therefore explore why some countries are more likely to experience economic crises, and why some countries typically experience shorter and less damaging crises. The paper updates an analysis I published four years ago in the European Journal of Political Economy. Both the original analysis and the new paper reach the same conclusion: economically freer countries perform much better during crises.

The analysis in the new paper rests on data from 389 crisis events between 1993 and 2017 in countries from around the world. I explore the risk of entering a crisis in the first place, the duration of the crisis, the time it takes to reach pre-crisis income again, and the full income loss during the crisis. Each of these four measures is associated with the Index of Economic Freedom from the Heritage Foundation. The analysis provides substantial support for the policy view from robust political economy, as more economic freedom is both associated with a lower risk of entering an economic crisis and a substantially smaller loss of income during the crisis. This is particularly the case for easier regulatory burdens and substantial market openness.

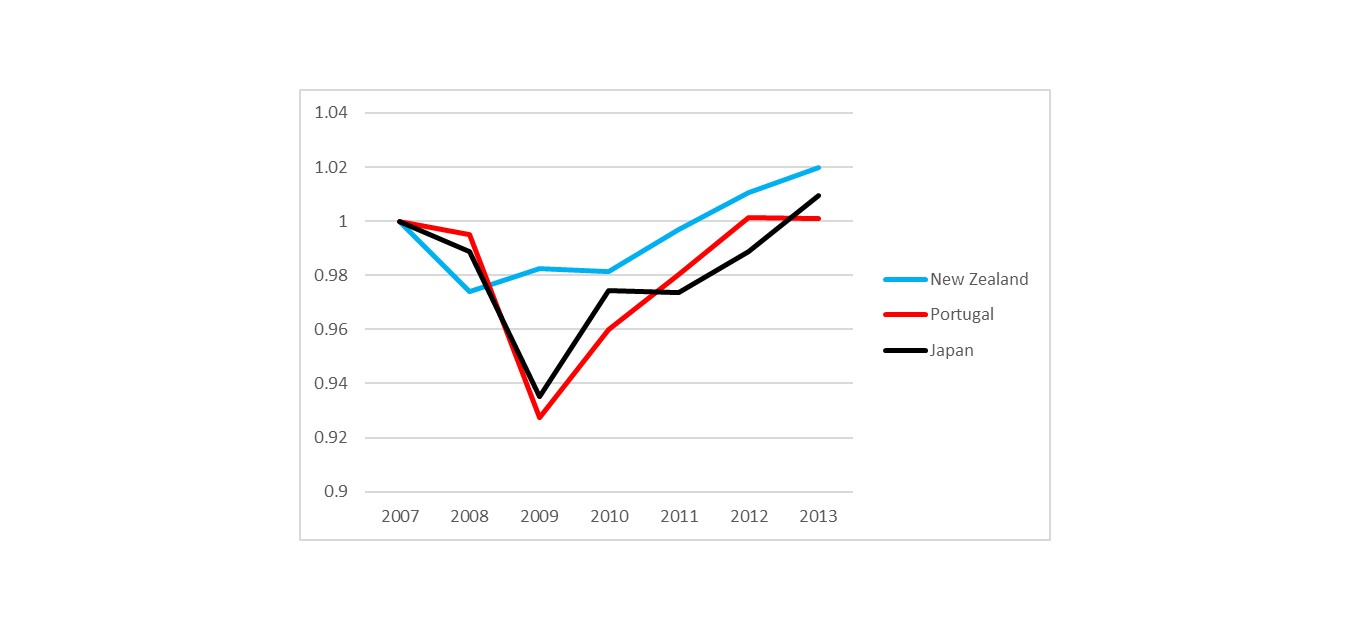

The figure below illustrates the main finding through three examples: the trajectory of GDP in New Zealand, Portugal and Japan during the 2008 financial crisis. Although one might think that New Zealand – as a small, open, peripheral economy – would prove to be more fragile during the crisis, being one of the economically freest societies in the world appears to have made it more resilient. Conversely, Portugal and Japan are closer to the global average and experienced much deeper economic crises around 2008.

In general, the estimates in the analysis suggest that had New Zealand been a typical Western country such as Austria, an economic crisis would on average result in an additional crisis loss per inhabitant of about £1,500. Noting that the Heritage Foundation assessment of market openness in rich countries varies between 62 in Greece and 86 in Australia (on a scale from 0 to 100), the effects in the analysis have both economic and political significance.

The bottom line and policy implication from such crisis research is quite simple: politicians and bureaucracies need to get out of the way of existing firms and new entrepreneurs. Countries that have more flexible labour markets and less regulated financial and product markets have fewer and easier crises, and this time is no different.