Fishy business

SUGGESTED

In practice, it has taken a long time to resolve the competing interests over fisheries and hammer out a new fisheries policy for the future. Indeed, we are still waiting to see the Government’s Joint Fisheries Statement (JFS). This will set out how these objectives will be met along with detailed Fisheries Management Plans for key stocks and fisheries in different geographical areas around our coast.

Fisheries policy rivals financial services in terms of the depth and extent of government regulation. Since the Fisheries Act was passed by Parliament in 2020, we have witnessed two years of protracted debate and consultation over what should be contained in the JFS.

Why do fisheries trigger such controversy?

The political controversy over fisheries policy is initially baffling when one considers that fishing represents a relatively small part of the UK economy. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), in 2021, the sector contributed a mere 0.03 percent of total UK economic output, and directly employed only 11,000 people, a fall of 9,000 since the mid-1990s. The number of fishing vessels in the UK fleet has also fallen by a third since 1996.[i]

But ocean trawlers represent a significant activity in certain outlying geographical regions of Britain – think Cornwall and the East coast of Scotland. What is more, in these areas, voters matter to the political parties, especially as they often reside in marginal swing seats.

Furthermore, there is a certain romantic aspect to fishing, which appeals to Country Life reading townies. Conservation of fisheries has also attracted the attention of leading campaigners, such as Sir David Attenborough; his fellow broadcaster Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall; along with Charles Clover, the Co-Founder and Executive Director of The Blue Marine Foundation and a prominent member of the ‘On The Hook’ campaign; and, of course King Charles III, who is an enthusiastic supporter of the Good Fish Guide, produced by the Marine Conservation Society.

These campaigners have exerted a strong influence on the public debate over fisheries, particularly among younger voters. The Good Fish Guide aims to show consumers which seafood options are the most sustainable by using a simple traffic light system. Green is the best option, Amber is okay, while Red indicates fish to avoid. No less than 161 fish options currently fall into the Society’s Red category.

A demand and supply mismatch

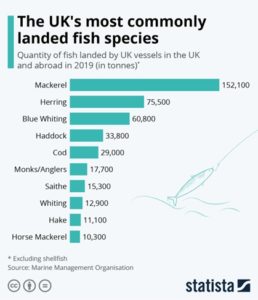

One of the curiosities of the UK fishing sector is that our fishing fleet catch a lot of fish which consumers shun. As the table reveals, our trawlers’ biggest catch includes several species which consumers tend to ignore, such as mackerel. Indeed, shoppers spent a mere £160,000 on fresh mackerel last year.

British consumers favour only five types of seafood when it comes to shopping, and two of these are imported from great distances. In fact, 80 percent of seafood bought in this country are accounted for the ‘Big Five’: cod, salmon, haddock, tuna, and prawns.

Furthermore, these five species have made up the majority of UK seafood sales for many years, despite high-profile campaigns to encourage consumers to eat a wider range of fish in order to take commercial fishing pressure off the Big Five species.

The Way Ahead

The Fisheries Act 2020 Act requires the UK fisheries policy authorities[ii] to publish what turns out to be 43 separate fisheries management plans (FMPs) to deliver the goal of sustainable fisheries. Each FMP will specify the stocks, type of fishing and the geographic area covered, as well as the authority or authorities responsible, and indicators to be used for monitoring the effectiveness of the plan.

In so far as this strategy does not involve a ‘one size fits all’ approach, it is to be welcomed, since each FMP is meant to be designed around the specific needs of their stocks, fisheries and location. This strategy would appear to have much in common with the approach advocated by Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom and her pioneering work on ‘bottom-up’ solutions to common-pool resource problems, exemplified by ocean fisheries. As Ostrom stresses, the key is to foster high levels of trust and reciprocity high levels of trust and reciprocity in systems of ownership and governance. This is exactly what has been conspicuously lacking in the top-down EU approach to fisheries management, where over-fishing has been a persistent and damaging characteristic.

Under the EU’s common fisheries policy over-exploitation of fish stocks was supposed to end in 2020. Yet, in practice, in 2021 more than 40 percent of all commercial stocks in EU waters were unsustainably fished, according to official monitoring data.[iii] One of the worst examples is the North Sea population of cod which has collapsed by 80 percent since the 1970s.[iv]

In her lecture to the IEA, shortly before her death, Elinor Ostrom noted, “One of the things we have found in our large-scale studies, much to the surprise of many people, is that local monitoring is one of the most important factors affecting resource conditions and the success of resource management systems in fisheries[v]”.

Over-fishing continues to be a crucial problem, as highlighted by campaigning organisations. Drawing on Ostrom’s work, a fruitful way forward is likely to involve better monitoring of fish stocks and fishing practices around our coasts. Yet as the State of Nature 2019 report pointed out[vi], up to only five per cent of fishing activity is monitored at sea, so there is considerable scope for abuses, such as ‘bycatching’ with inappropriate nets, which inevitably leads to fish from different species being caught up in large nets designed to capture entire shoals of fish. Many of these fish are tossed back into the sea, but do not survive.

The practicalities of monitoring and husbanding our fisheries will continue to be a perennial challenge, but with the use of new technology, such as purpose-designed drones, and the adoption of best practice avoidance measures to reduce the number of unwanted fish caught, the ability to manage these scarce resources should become easier. Much rests on the ability to effectively enforce these detailed regulations.

One ray of hope is reflected in the fact that over the last 12 years, the ‘Typical Length Indicator’ employed for measuring fish catches has begun to show signs of improvement, particularly for demersal fish such as plaice and turbot. The onus is now on the UK to show how it can manage its fisheries in a more sustainable manner than those member states regulated by the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy.

Keith Boyfield is an IEA Regulation Fellow

___

Recommendations for further reading:

- “Net Gain: Opportunities for Britain’s fishing industry post-Brexit” by Shanker Singham (2018)

- “Sea Change: How markets & property rights could transform the fishing industry” by Richard Wellings (ed.) (2017)

- “Fisheries policy outside the EU: A Briefing” by Philip Booth (2016)

_____

[i] UK Fisheries Statistics, House of Commons Library, published 11 October 2022, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn02788/

[ii] Defra, and the devolved administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

[iii] The Guardian, 25 March 2022

[iv] ibid.

[v] ‘The Future of the Commons Beyond Market Failure and Government Regulation’, by Elinor Ostrom et al, IEA Occasional Paper 148, pages 82-83, published in 2012.

[vi] State of Nature 2019 report, page 61, https://nbn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/State-of-Nature-2019-UK-full-report.pdf