Chequers – what might have been

SUGGESTED

Here, we take a red pen to the Chequers statement.

In his influential memo analysing the statement, Martin Howe QC concluded that “the Chequers proposals would involve the permanent continuation in the UK of all EU laws which relate to goods, their composition, their packaging, how they are tested etc in order to enable goods to cross the UK/EU border without controls. All goods manufactured in the UK for the UK domestic market, or imported from non-EU countries, would be permanently subject to these laws.”

In other words, the proposal would entail the judgements of the ECJ continuing to apply in the UK, albeit indirectly and would impair, if not eliminate, the UK’s ability to conduct an independent trade policy. Instead of this “regulatory tar pit”, with UK manufacturers and importers bound by laws that the UK has had no say in, what might a position of the future relationship, absent this commitment to ongoing harmonisation, look like?

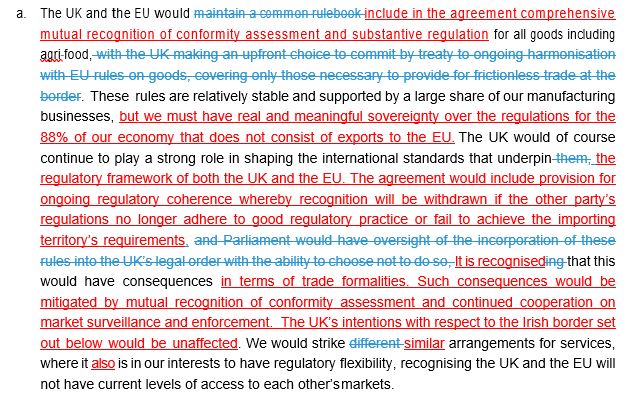

Well on regulations, it might have looked something like this:

A free trade agreement that acknowledges and builds on the UK and EU’s unprecedented starting point of regulatory harmonisation and recognition, WTO disciplines on national treatment and technical barriers to trade, and a shared interest in maintaining trade links and supply chains.

Critically, the UK should not be proposing to stay harmonised on state aid – though it should certainly be accepting disciplines to ensure fair trade in this sense, as is usual in free trade agreements. Britain should not be looking for a lock in to “current levels” of horizontal regulations on environmental, employment and consumer matters – not because we would be envisaging lowering standards in these areas, but because, especially if coupled with a right for the ECJ to interpret EU rules, any changes we might wish to make in these areas to improve UK competitiveness would likely be seen as “falling below” current levels. So that wording has to go, but we can certainly accept the more usual kind of FTA commitment on this area.

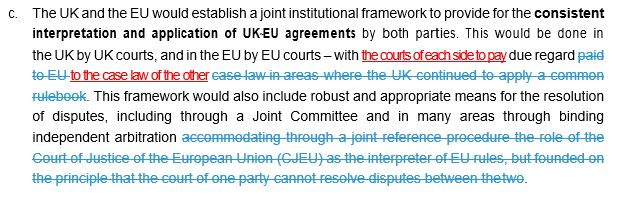

This also indicates that a right for the ECJ to be the interpreter of the rules we apply in the UK under the sovereignty of parliament would no longer be relevant if we are not operating a common rule book. Moreover, in international law it is usual for the courts of each side to pay due regard to the case law of the other, so this should be a bit more balanced:

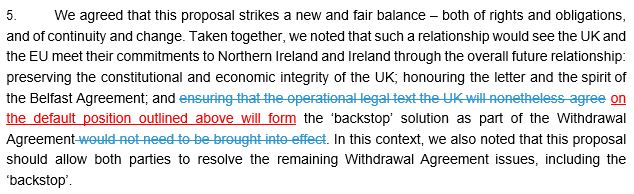

And finally, customs and the Irish border. An untested facilitated Customs Arrangement would likely violate WTO rules and would certainly deter trade partners from striking a deal on tariffs, as their exporters could not be certain to be able to benefit from any preference the UK purported to grant. Instead of persisting with this model, the UK should be proposing a highly streamlined customs arrangement:

Ah, but what about the Irish border and the backstop? Should this have been the backstop?

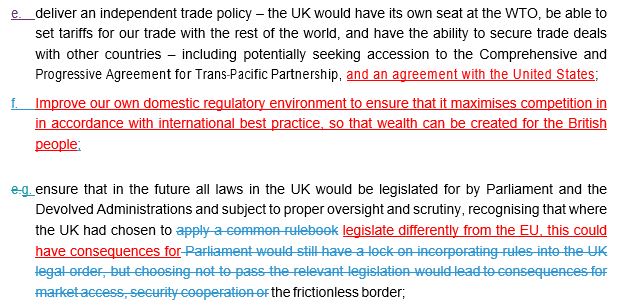

As to the benefits, well, there are quite a few that the Cabinet forgot about at Chequers:

1 thought on “Chequers – what might have been”

Comments are closed.

Ok we agree the PM’s (sorry, Ollie Robbins’) plan is a “turd” but what is the alternative?

IEA is part of the problem. It has not provided one yet dismissed Import Excess Tax, the best Brexit policy model to date, citing unspecified doubts about legality (how ? it is NOT illegal), the admin burden (really – compared

to Max Fac etc.???) queried its Free Trade credentials ( it’s a facilitator of free trade).

Read about Import Excess Tax again Julian and Shankar then either get behind it or propose a better one, original and not re-hashes of Canada, Norway, Swiss, Turkish etc. models.