Why the current strike wave is not a 1970s re-enactment

SUGGESTED

It looks as though total working days lost during the year to June will have reached between 4 and 5 million. This may be minor league compared with just a whisker under 30 million in 1979 (in a much smaller workforce), but it’s still going to be the highest figure since 1989.

One major difference from the Bad Old Days is that the current batch of strikes is almost entirely in the public sector. What about the railways, though, weren’t they privatised? They were, of course, in a rather unsatisfactory way. But the infrastructure was renationalised as Network Rail two decades ago, while since Covid the Train Operating Companies (TOCs) now simply perform to contracts specified in piddling detail by the Department for Transport, having no influence over fares and timetables and simply receiving a small management fee for their trouble. They have no real independence, and the Rail Delivery Group, which negotiates for the TOCs, can do nothing without the Department for Transport’s say-so. Recognising this, the Office of National Statistics now classifies TOC staff as public sector employees.

This round of strikes is taking a long time to resolve. Why is this? Economists have written little about strikes in recent years, as unions and their activities had largely disappeared from a labour market agenda which has been much more centred on such issues as minimum wages, employment regulation, flexible work and the gig economy.

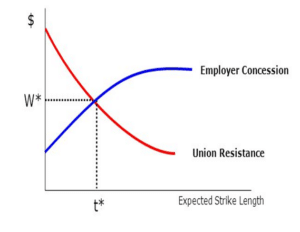

The classic way in which economists analysed strikes in the last century is in the framework developed by Sir John Hicks in the 1930s. This is illustrated below.

Hicks posits a situation where employer and union are initially miles apart. The union makes a high wage demand, while the employer makes a paltry offer. A strike results. As the strike proceeds, both sides incur costs and adjust their position. The ‘union resistance curve’ slopes downwards, flattening out at a very low wage rate where workers would leave the job; the ‘employer concession curve’ slopes upward, but reaches a maximum where paying a higher wage would bankrupt the firm. As the diagram indicates, there will be a wage rate at which these curves cross, and this is where a settlement can occur. Both parties will be worse off if the strike continues beyond t*.

Hicks discusses the factors which determine the position and shape of these curves, but he also makes the important point that a strike could be avoided if each party knew with certainty the true costs faced by the other. Then they could proceed to the settlement at W* without the need for a strike, with both parties better off.

Needless to say, the parties don’t know each other’s true position – indeed they both initially have an incentive to conceal it. So Hicks argues that anything which brings the parties together – extended negotiations, conciliation services and so on – helps to increase knowledge of the other side’s position and will hasten a settlement. This became the orthodoxy in industrial relations thinking in the postwar period.

There’s a lot to be said in favour of this way of thinking about strikes. It was to be built on in the 1980s by John Addison and Stan Siebert who saw strikes being caused by disruption to bargaining expectations, with greater uncertainty (‘accidents’ such as unanticipated inflation) leading to more strikes. It does suggest that strikes will end sooner rather than later, and that both parties are rational in a narrow sense of wanting to do the best they can.

But it is a model of the behaviour of private sector employers, who have to reach a settlement to stay in business, and unions (and their members) with few resources to fall back on. Moreover strikes are now no longer for the continuous extended period assumed by Hicks. Public sector unions, with significant strike funds and members who are normally better off than private sector workers, typically strike for a day or a few days at a time. The costs to members are slight, and in some cases made up for in overtime later. Meanwhile public sector employers are under little compulsion to reach a settlement. Their ‘business’ may be disrupted by strikes, but the civil service or schools or the passport service won’t go bust: indeed they may save money. So strikes can drag on indefinitely.

Whereas private sector strikes are aimed at imposing costs on employers, public sector strikes are clearly undertaken to impose costs on the public – parents whose children can’t go to school, NHS patients who have to wait for treatment, university students whose lectures are cancelled. The aim is to get the public so vexed that they turn on the government, which is then forced to settle.

Moreover public sector activists are often not in it just to increase pay. Some quite explicitly want to bring down the government. More moderate souls demand more staff be employed (a rare demand in the private sector) and that policy should change – for instance that NHS services should not be contracted out, or that Ofsted scrap school inspections. And, as we see on the railways, productivity bargains to boost pay – which sometimes work in the ‘real’ private sector, where trade-offs are more common and negotiators less absolutist – are anathema.

So what of the current strike situation? The government faces an obduracy which has surprised many commentators. It could always give in and acquiesce to union demands for inflation-busting pay increases. But the dreadful experience of wage-price spirals in the 1970s and 1980s, which most of us thought banished to the history books, coupled with the dire fiscal position, argues strongly against this.

A determined government could do something dramatic, like banning strikes in some sectors, or imposing compulsory arbitration, or perhaps reverting to something which hasn’t been used for many decades – the lockout. Under this, younger readers may not be aware, the employer just closes the business to employees and doesn’t reopen till they accept the terms it lays down.

Although this is legal, a private sector employer trying this would inevitably find itself bogged down in all sorts of legal battles. The government could in principle have a go, though the current administration would run miles from the idea (as we saw with P&O’s similar ‘fire and rehire’ episode last year).

To be fair, it has made it possible to recruit agency workers to fill in for striking employees, and belatedly required minimum service levels during strikes. These measures may have some slight impact in the future, but not now.

The position at the moment seems to be just to accept continuing levels of disruption in the hope that the public will put up with it while union members grow tired of endless ineffective strikes, and eventually just take the money on the table. It’s not satisfactory from anyone’s viewpoint, but may be all we can expect from a government which seems to have run out of steam.