Steel tariffs: “pork barrel politics” in action?

SUGGESTED

“We are re-emerging after decades of hibernation as a campaigner for global free trade. And frankly it is not a moment too soon because the argument for this fundamental liberty is now not being made […]

Free trade is being choked and that is no fault of the people, that’s no fault of individual consumers, I am afraid it is the politicians who are failing to lead. The mercantilists are everywhere, the protectionists are gaining ground. From Brussels to China to Washington tariffs are being waved around like cudgels…”

We might have hoped that a Prime Minister seemingly committed to ‘Global Britain’ could be relied upon to understand his own argument, and for it not merely to be a warning about his own future intentions. Alas, the leader, who was once described by his own former advisor as a “shopping trolley smashing between aisles”, now wants to put up the cost of making shopping trollies by extending ‘defensive’ tariffs of 25% of steel products above set quotas from specific countries or territories.

Tariffs are primarily a tax on buying things, not selling them, a tax paid for primarily by your own people and businesses, not foreign competition. Tariffs add to the ‘cost-of-living’ crisis by raising domestic prices. They contribute to economic instability by encouraging retaliatory action, which in turn reduces the competitiveness of your own exports, leading to unemployment, lost orders, reduced investment, and offsetting losses to any tariff gains. They distort global supply chains that may then take years to return even after the tariffs have lapsed. They reduce the ability of the nation to conclude free trade deals, because stability and trust matters in making such agreements last. They are all the things Johnson warned Johnson they would be in that Greenwich speech. Free-trade liberals therefore do not support tariffs under any circumstances.

But the soggier form of liberalism that exists in world trade rules, and in the UK under the remit of the Trade Remedies Authority (TRA), accepts a few exemptions. These are:

- Anti-dumping – blocking efforts to sell goods below their cost of production

- Anti-subsidy – to remedy unfair competition from foreign Government support for their exporting industries.

- Safeguarding – ‘emergency’ actions in reaction to increased imports of goods where these might cause ‘serious injury’ to domestic industry.

In the UK it is the role of the TRA to assess requests for such measures under these terms, and for the Secretary of State for International Trade to decide. Our current remedies were inherited from the EU’s trade regime, and the TRA took over the functions of an interim predecessor body in June 2021. A key difference with the EU system is an ‘economic interest test’ for whether remedies are justified, presumed met in the case of anti-dumping and anti-subsidy cases, but more nuanced and open to political interference in the case of safeguarding. The history of this steel decision is one of inherited remedies from 2018, being reconsidered (i.e. ended) in 2021, then the reconsideration being reconsidered at the behest of the Minister, leading to a 273-page report that gives the Minister justification to extend most of the measures for a further 3 years. In brief the TRA considered that the harm done to consumers of steel products would be less than the benefit to the UK’s £2.2bn steel industry, thus the economic interest test was met, bar for 17 out of 253 product codes where UK domestic industry was tiny.

Under its own terms and the regulations then the decision was justified, although could be disputed at the level of the World Trade Organization, leading to a further discussion as to whether the UK was ‘breaking international law’. But the very idea that there is a branch of government dedicated to determining that in July to September 2021 no more than 9,106 tonnes of steel products from India should be tariff-free, whereas by April to Jun 2024 it should 9,530 tonnes, and any imports from Lesotho should be tariff-free, underwrites the free market case. The shorter and more honest version of the TRA case is that politicians like the steel industry and hate bad headlines, such as those arising from plant closures. The TRA reports notes that the global steel products market has enough surplus capacity to support UK domestic demand for 80 years! Or in other words across the world politicians are claiming as ours do that steel is a ‘strategic industry’ and contributing to a massive case of over-supply. They can’t all be right, and the case for comparative advantage in the UK is thin to the point of absurd. Particularly given domestic policies that damage the competitiveness of heavy industry by putting up the cost of energy, labour and land.

Going further under the skin of the politics, the likely cause of this latest example of Johnson’s incoherence is not economic but deeply political. It is unlikely he has followed Trump and Biden down the poison path of domestic protectionism as an ideological stance, let alone in the belief it will do any good. The PM instead believes he needs to secure ‘Red Wall’ MP votes to stave off another confidence vote in his leadership. Given he only narrowly won in June by 63 votes, a mere 32 MPs changing their minds would seal his fate, something that greatly enhances the bargaining power of those remaining loyal. Focused constituency interests, such as the viability of a local steel mill or forgings plant, become more important. The wider or national interest such as access to good quality cheap steel for a host of other industries, becomes less so. This is exactly the kind of ‘pork barrel’ politics for local interests that undermines coherent economic policy in the US. It is usually far less common or obvious in the UK.

There are far more constituencies that contain the victims of steel tariffs – e.g. the automotive, aerospace, and construction products industries, or the metals processing and machinery makers whose costs will remain artificially high – than constituencies that contain primary steel manufacturing mills or steel products processing plants. But as noted, for them, the impact is more thinly spread and buried in wider inflation challenges across all markets.

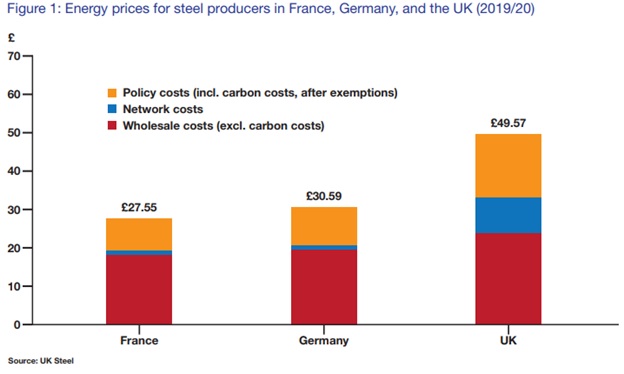

Meanwhile a principal cause of UK Steel woes remains unaddressed. Steel making is an energy intensive industry, some 20% of the costs of production are power prices (rooted in coal, gas and grid access, dependent on process). Even before the latest global crisis, even after accounting for multiple special policy exemptions, UK makers were paying near double those paid in France and Germany, and over 50% more than the EU average.

The more logical step for Johnson to take to give UK steel businesses a chance would be to radically reform UK energy markets and land taxes like business rates, remove state aid from renewable industries and nuclear, unblock access to domestic coking coal, lift the moratorium on fracking, or otherwise cut the cost of doing business through lower taxes and regulatory reform. All things that contain the bonus of not starting a trade war or a cascade of unintended consequences and higher costs throughout UK manufacturing supply chains.

But here the PM with his affection for policy cakeism wants simultaneously to lead the world in the UK’s transition to Net Zero and retain heavy industry. He wants wind turbines made here rather than imported, while putting up the cost of making them here, thereby guaranteeing imports. He and his predecessors have created a green growth paradox where green industrial strategy undermines green industrial growth.

Most of all however he wants to remain as the one cutting the cake, and on that basis we might expect the administration to stand for more incoherence, more hi-vis jacket moments, and an ever growing raft of micro-interventions in the UK economy, with door-step report justifications, instead of the free markets and free trade promised in 2020. Extending steel tariffs is a small policy, but large signal of future intent.