Verdict on John McDonnell’s labour market policies: each measure is bad individually; the package is worse than the sum of the parts

SUGGESTED

All employment rights will now begin ‘from Day 1’: this would seem to mean, for example, that probationary periods will become a thing of the past and it will be difficult to dismiss even individuals who show themselves incompetent from the start.

New employees will be able to demand flexibility in their working arrangements before they have even settled into a routine. Employers will surely react to this by being ultra-cautious in recruitment and avoid taking risks on employees without a strong existing track record (such as young workers and immigrants), or female workers who seem most likely to take time off for childcare.

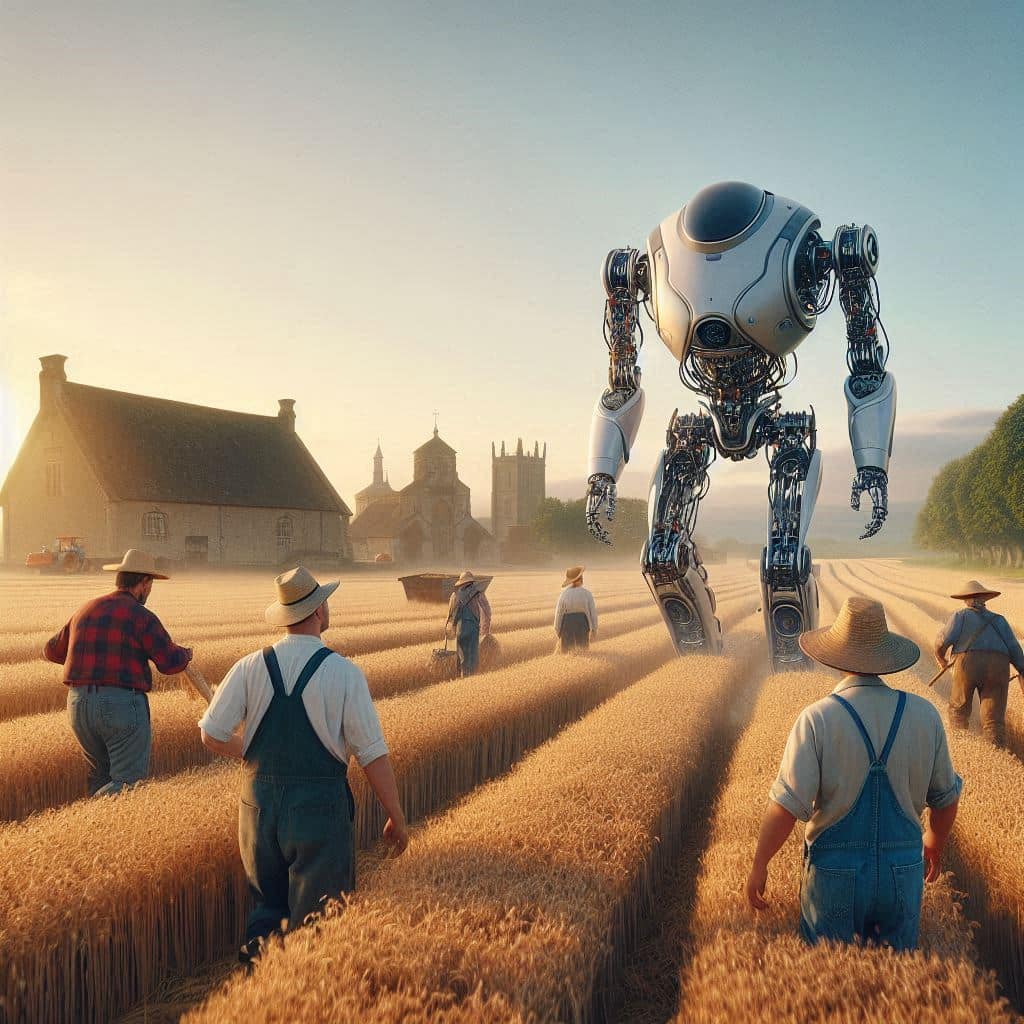

All workers will be paid a higher National Living Wage of £10 an hour, with no differential for age. This is likely to encourage further automation of low-skilled jobs and a reduction of opportunities for young workers.

Any exemptions from the Working Time Directive will be banned; this will make it very difficult to staff jobs where there are irregular working hours outside normal workplaces: police patrols, fishing, transport and so on. Higher costs and more unreliable services seem likely.

Hours and other working conditions will be set by sectoral collective bargaining, with increased powers for unions and reduced competition. This is a model which the Germans, for example, have moved away from because of its doleful effects on competition and productivity.

Companies will be obliged to gift shares to workers and allow board level representation to employees (in most cases these will be trade union activists). Depending on how legislation is shaped, this will tend to discourage firms from being listed in the UK and will encourage production abroad for the UK market rather than domestic production and employment.

Local authorities will be obliged to take back outsourced services and employ staff directly. This will produce considerable disruption in the short run, as outside providers run down provision and local authorities struggle to take responsibility back. It will be a costly exercise and in the medium-term financial constraints are likely to lead to cutbacks in services and employment.

Banning zero-hours contracts will reduce employment opportunities for many workers such as students, those with changing care responsibilities, older workers and people who want to do occasional extra work on top of their ‘regular’ job (these include many professionals). The extra cost associated with guaranteeing employment will almost certainly lead to a reduction in the total hours offered by employers, and will be a further incentive to automation.

Despite the caution shown by the recent Skidelsky report, Labour is now apparently signed up to a four-day (or 32-hour) week with no reduction in pay. Even if brought in over an extended period, this must raise costs (and ultimately reduce employment prospects) in those jobs where productivity is very difficult to increase because of the nature of the work – heart surgeons, teachers, orchestras, fitness trainers.

The UK’s labour market has shown itself remarkably able to absorb a constant flow of new regulations over the last twenty years and yet maintain low levels of unemployment while increasing the number and range of new jobs and a gradual, albeit erratic, increase in real wages. Businesses have found ingenious ways of opening up opportunities for new groups of workers and new lifestyles, and for getting round ill-thought-out restrictions whether from UK politicians or European Directives.

While we might question the need for and desirability of some of these new Labour Party policies, in isolation they would not be too devastating. However, making all these changes in a short period of time is likely to mean a collapse in employment prospects, paradoxically especially for the most vulnerable workers – young people, immigrants and female returners – which Mr McDonnell claims to wish to help.